玻璃

编辑玻璃是一个非结晶的,无定形固体,其通常是透明的并且在窗玻璃,餐具和光电子学中具有广泛的实用、技术和装饰用途。最熟悉且历史上最古老的人造玻璃是基于化合物二氧化硅的“硅酸盐玻璃”,主要成分为沙。在流行的用法中,术语玻璃通常仅用于指代这种类型的材料,其在用作窗玻璃和玻璃瓶中是常见的。在现有的许多硅基玻璃中,普通玻璃和容器玻璃是由一种称为钠钙玻璃的特定类型组成,含约占75%二氧化硅(SiO2)、来自碳酸钠(Na2CO3)中的氧化钠(Na2O)、氧化钙(CaO) ,也称为石灰,和几种微量添加剂。

硅酸盐玻璃的许多应用源于它们的光学透明性,使其主要用作窗玻璃。玻璃透射,反射和折射光线;通过切割和抛光可以增强这些特质,从而制造光学透镜,棱镜,精细玻璃器皿和光纤,用于通过光进行高速数据传输。玻璃可以通过添加金属盐来着色,也可以用玻璃质瓷漆进行涂漆和印刷。这些特质导致玻璃在艺术品的制造中有着广泛的应用,特别是彩色玻璃窗。硅酸盐玻璃虽然易碎,但非常耐用,早期玻璃制造文化中就有许多玻璃碎片的例子。由于玻璃可以形成或模制成任何形状,因此传统上用于容器:碗,花瓶,瓶子,罐子和水杯。在其最坚固的形状,它也被用于纸镇,大理石和珠子。当挤出成玻璃纤维并以捕获空气的方式铺成玻璃棉时,它变成绝热材料,当这些玻璃纤维嵌入有机聚合物塑料中时,它们是复合材料玻璃纤维的关键结构增强部分。历史上一些物体通常由硅酸盐玻璃制成,它们简单地通过材料的名称来称呼,例如水杯和眼镜。

从科学上讲,“玻璃”一词的定义往往更为宽泛,包括在原子尺度上具有非结晶(即无定形晶态)结构的每一种固体,当加热到液态时,它们都表现出玻璃化转变。日常使用中常见的陶瓷和许多聚合物热塑性塑料是玻璃。这种玻璃可以由不同于硅的材料组成:金属合金、离子熔体、水溶液、分子液体和聚合物。对于许多应用,如玻璃瓶或眼镜,聚合物玻璃(丙烯酸玻璃,聚碳酸酯或聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯)是比传统玻璃更轻的选择。

目录编辑

1 硅酸盐玻璃编辑

1.1 成份

二氧化硅(SiO2)是玻璃的常见基本成分。[1]在自然界中,石英的玻璃化发生于闪电击中沙子时,形成中空的,分枝状根茎名为闪电。[2]

熔融石英是由化学纯二氧化硅制成的玻璃。它具有优异的抗热冲击能力,能够在炽热时在水中存活。然而,它的高熔化温度(1723 °C )和粘度使其难以使用。[3]通常,添加其他物质是为了简化加工。一种是碳酸钠(Na2CO3,“苏打”),它降低玻璃化转变温度。苏打使玻璃水溶,这通常是不希望的,所以石灰 (CaO,氧化钙,通常从石灰石中获得),一些氧化镁 (MgO)和氧化铝 (Al2O3)的加入以提供更好的化学耐久性。所得玻璃含有约70-74%重量的二氧化硅,被称为钠钙玻璃。钠钙玻璃约占人造玻璃的90%。[4][5]

大多数普通玻璃含有其他成分来改变其性质。铅玻璃或燧石玻璃更“明亮”,因为增加的折射率导致明显更多的镜面反射和增加的光色散。添加钡也会增加折射率。二氧化钍赋予玻璃高折射率和低色散,以前用于生产高质量的透镜,但由于其放射性,已被现代眼镜中的氧化镧取代。[6]铁可以掺入玻璃中以吸收红外辐射,例如在电影放映机的吸热滤光器中,而铈(IV)氧化物可以用于吸收紫外波长的玻璃。[7]

以下是更常见类型的硅酸盐玻璃及其成分、性能和应用:

- 熔融石英,[8]也被称为熔融石英玻璃,[9] 玻璃质-石英玻璃:二氧化硅(SiO2)呈玻璃状(即其分子无序且无规的,没有晶体结构)。它的热膨胀非常低,非常坚硬,并且耐高温(1000-1500℃ )。它也最耐风化(在其他玻璃中,由于碱离子从污染中浸出而同时染色引起的浸出)。熔融石英用于高温应用,如炉管、灯管、熔化坩埚等。[10]

- 钠钙硅玻璃,窗玻璃:[11]二氧化硅+氧化钠(Na2O) +石灰(CaO) +氧化镁(MgO) +氧化铝(Al2O3)。[12][13]它是透明的,[14]易于成型,最适用于窗玻璃。[15]它热膨胀率高,耐热性差[14](500–600℃)。[10]它用于窗户、一些低温白炽灯泡和餐具。[16] 容器玻璃是一种钠钙玻璃,与平板玻璃略有不同,平板玻璃使用更多的氧化铝和钙,钠和镁更少,而钠和镁更易溶于水。这使得它不太容易受到水侵蚀。

- 硼硅酸钠玻璃,派热克斯:二氧化硅+ 三氧化二硼 (B2O3)+苏打(Na2O) +氧化铝(铝2O3)。[17]其比窗玻璃更耐热膨胀。[9]用于化学玻璃器皿、烹饪玻璃、汽车照明灯等。硼硅酸盐玻璃(例如派热克斯、杜兰)的主要成分为二氧化硅和三氧化二硼。它们具有相当低的热膨胀系数(7740 Pyrex CTE是3.25×10-6/ ℃[18],而典型的钠钙玻璃的热膨胀系数为9×10-6/ ℃[19]),使它们在尺寸上更加稳定。较低的热膨胀系数(CTE)也使它们较少受到由热膨胀而引起的应力的影响,因此不容易受到热冲击的破坏。它们通常用于试剂瓶、光学元件和家用炊具。

- 氧化铅玻璃,水晶玻璃,[10] 铅玻璃:[20]二氧化硅+氧化铅(PbO) +氧化钾(K2O) +苏打(Na2O) +氧化锌(ZnO) +氧化铝。由于其高密度(导致高电子密度),它具有高折射率,使玻璃器皿的外观更加明亮[21](称为“水晶”,尽管它当然是玻璃而不是水晶)。它还具有很高的弹性,使玻璃器皿成为“环”。它在工厂里也更可行,但不能很好地忍受加热。[10]这种玻璃也比其他玻璃更易碎[22]并且更容易切割。[21]

- 铝硅酸盐玻璃:二氧化硅+氧化铝+石灰+氧化镁[23]+氧化钡(BaO)[10]+氧化硼(B2O3)中。[23]广泛用于玻璃纤维,[23]用于制造玻璃增强塑料(船、钓鱼竿等)。)和卤素灯泡玻璃。[10]铝硅酸盐玻璃也耐风化和水侵蚀。[24]

- 氧化锗玻璃:氧化铝+ 二氧化锗 (GeO2)中。极其透明的玻璃,用于通信网络中的光纤波导。[25]光通过1千米长的玻璃纤维仅损失5%的强度 。[10]

另一种常见的玻璃成分是粉碎的碱性玻璃或“碎玻璃”,可用于回收玻璃。回收玻璃节省原材料和能源。碎玻璃中的杂质会导致产品和设备故障。可以加入澄清剂如硫酸钠、氯化钠或氧化锑,以减少玻璃混合物中气泡的数量。 玻璃批量计算是确定正确原料混合物以获得所需玻璃成分的方法。[26]

Moldavite是一种陨石撞击形成的天然玻璃,产自波西米亚的贝塞斯

闪电管石块

石英砂(二氧化硅)是工业玻璃生产的主要原料

三位一体核武器试验制造的玻璃

铅玻璃,在玻璃中加入氧化铅制成的玻璃

硼硅酸盐玻璃吉他幻影

2 物理性质编辑

2.1 光学特性

玻璃的广泛使用主要是由于生产出对可见光透明的玻璃组合物。相反,多晶体材料通常不透射可见光。[27]单个微晶可以是透明的,但是它们的小平面(晶界)反射或散射光,导致漫反射。玻璃不包含与多晶体中晶界相关的内部细分,因此不会像多晶材料那样散射光。玻璃的表面通常是光滑的,因为在玻璃形成过程中,过冷液体分子不会被迫处理成刚性的晶体几何形状中,并且可以遵循表面张力,这会产生了微观上光滑的表面。即使玻璃部分吸光,即着色,这些赋予玻璃透明度的特性也可以保持。[28]

玻璃具有折射、反射和透射遵循几何光学的光的能力,[29]而不会散射(因为没有晶界)。[30]它用于制造镜片和窗户。[31]普通玻璃的一个折射指数大约1.5。[32]这可以通过添加低密度来变修改[33]例如降低折射率的硼(见冠状玻璃),[34]或者用高密度材料例如(传统的)氧化铅(参见含铅玻璃和铅玻璃)或在现代使用中,毒性较低的氧化物锆、钛、或钡。这些高折射率玻璃(在玻璃器皿中使用时被不准确地称为“晶体”)会产生更多彩色光的色散,并因其钻石般的光学特性而备受推崇。

根据菲涅耳方程,玻璃板的反射率约为每表面4%(在空气中垂直入射时),[35]并且一种元件素(两个表面)的透射率约为90%。[36]具有高氧化物锗含量的玻璃也可应用于光电子学,[37]例如,对于透光光纤。[38]

简易光学装置:放大镜

光玻璃纤维束

2.2 其他属性

在制造过程中,硅酸盐玻璃可以被浇注、成型、挤出和模塑成从平板到高度复杂形状的各种形式。[39]成品很脆[40]并且会断裂,除非层压或经过特殊处理,[41]但是在大多数情况下非常耐用。[42]它侵蚀得非常慢[43]并且能大部分都承受水的作用。[44]它最能抵抗化学攻腐蚀[45]不与食物反应,是制造食品和大多数化学品容器的理想材料。[46]玻璃也是一种相当惰性的物质。[47]

腐蚀

尽管玻璃通常是耐腐蚀性的[48]并且比其他材料更耐腐蚀,但它仍然会被腐蚀。[42]组成特定玻璃成分的材料对玻璃腐蚀的速度有影响。[45]含有高比例碱的玻璃[49]或者碱土金属的耐腐蚀性不如其他种类的玻璃。[50]

玻璃鳞片有防腐涂层的应用。[51]

力量

玻璃的拉伸强度通常为7兆帕(1000 psi),[52]然而,理论上它可以有一个强度17千兆帕,因为玻璃有很强的化学键。几个因素,如划痕和气泡等缺陷[53]以及玻璃的化学成分会影响玻璃的拉伸强度。[54]几种工艺如增韧可以提高玻璃的强度。[55]

3 当代生产编辑

在玻璃批料制备和混合之后,将原料输送到熔炉中。用于大规模生产的钠钙玻璃在燃气单元中融化。特种玻璃的较小规模熔炉包括电熔炉、罐式熔炉和日用储罐。[56]经历熔化、均质化和精制(去除气泡)后,玻璃才会成形。用于窗户和类似应用的平板玻璃是由浮法玻璃工艺形成的,这一过程是在1953年到1957年间由英国皮尔金顿兄弟的Alastair Pilkington爵士和肯尼斯·比克斯塔夫(Kenneth Bickerstaff)使用熔融锡槽创造了连续的玻璃带,在重力的影响下不受阻碍地流动。玻璃的顶部表面在压力下经受氮气以获得抛光表面。[56]用于普通瓶和罐的容器玻璃是通过吹制和压制的方法形成的。[57]这种玻璃通常经过轻微的化学改性(添加更多的氧化铝和氧化钙),以提高耐水性。玻璃成形技术的表格进一步总结了其他玻璃成形技术。

一旦获得所需的形状,玻璃通常被退火,以消除应力并增加玻璃的硬度和耐久性。[58]随后可进行表面处理、涂层或层压,以提高化学耐久性(玻璃容器涂层内璃容器)内部处理、强度(钢化玻璃、防弹玻璃、挡风玻璃[59]),或光学性能(隔热玻璃,抗反射涂层)。[60]

杂质使玻璃具有颜色

透明和不透明示例

玻璃可以吹成众多的形状

3.1 颜色

玻璃中的颜色可以通过添加均匀分布的带电离子(或色心)和通过沉淀精细分散的颗粒(例如在光致变色玻璃中)来获得。[61]普通钠钙玻璃薄时肉眼看起来无色,尽管氧化铁 (FeO)杂质高达0.1%重量[62]产生绿色,这可以用厚片或借助科学仪器观察。进一步FeO和氧化铬 (Cr2O3)添加物可用于生产绿色瓶子。硫与碳和铁盐一起用于形成铁多硫化物,并产生黄色到几乎黑色的琥珀色玻璃。[63]玻璃熔体也可以从还原性燃烧气氛中获得琥珀色。[64] 二氧化锰可以少量添加,以去除氧化铁(ⅱ)产生的绿色。艺术玻璃和工作室玻璃使用严密保护的配方着色,包括金属氧化物、熔化温度和“烹饪”时间的特定组合。艺术市场上使用的大多数有色玻璃是由服务于该市场的供应商批量生产的,尽管有些玻璃制造商能够用原材料制造自己的颜色。

4 硅酸盐玻璃的历史编辑

天然玻璃,尤其是火山玻璃黑曜石,被全球许多石器时代社会用于生产锋利的切割工具,并且由于其来源区域有限,被广泛交易。考古证据表明,第一个真正的玻璃是在叙利亚北部沿海、美索不达米亚或古埃及制造的。[65]公元前三千年中期,已知最早的玻璃物体是珠子,可能最初是作为金属加工 ( 炉渣)的意外副产品产生的,或者是在生产彩釉过程中产生的,彩釉是一种通过类似上釉的工艺制成的玻璃前材料。[66]

玻璃仍然是一种奢侈品,超过青铜时代晚期文明的灾难似乎已经是玻璃制造停滞不前南亚玻璃技术的本土发展可能始于公元前1730年。[67]然而,在古中国代中与陶瓷和金属制品相比,玻璃制造似乎起步较晚。术语玻璃发展于后期罗马帝国。那它位于特里尔的马玻璃以制造心特,在在现代德国晚期拉丁语学术语lesum起源于日耳曼语,代表透明的,有光泽的物质。[68]罗马帝国各地都发现了玻璃物品[69]在国内,葬礼,[70]和工业环境。[71]罗马玻璃的例子已经在前罗马帝国之外的中国,[72]波罗的海、中东和印度被发现。[73]

玻璃在中世纪被广泛使用。在对定居点和墓地的考古挖掘中,英格兰各地都发现了盎格鲁撒克逊玻璃。[74]盎格鲁撒克逊时期的玻璃被用于制造一系列物品,包括容器、窗户,[75]珠子,[76]也用于珠宝。[77]从10世纪起,玻璃被用于教堂和大教堂的彩色玻璃窗户,沙特尔主教座堂和圣丹尼斯大教堂有着著名的例子。到了14世纪,建筑师们正在设计带有彩色玻璃墙的建筑,例如圣礼拜堂,巴黎,(1203–1248)[78]和格洛斯特大教堂的东端。[79]彩色玻璃在19世纪随着哥德复兴式建筑的出现有了重大复兴。[80]随着文艺复兴和建筑风格的改变,大型彩色玻璃窗的使用变得不那么普遍。[81]家用彩色玻璃的使用增加了[82]直到大多数坚固的房子都有玻璃窗。这些玻璃最初是由小块玻璃引线在一起的,但随着技术的变化,玻璃可以用越来越大的板材相对便宜地制造。这导致了更大的窗玻璃,在20世纪,普通家庭和商业建筑中的窗户变得更大。

在20世纪,新型玻璃如夹层玻璃、强化玻璃和玻璃砖[83]增加了玻璃作为建筑材料的使用,并带来了玻璃的新应用。[84]多层建筑通常用几乎完全由玻璃制成的幕墙建造。[85]类似地,夹层玻璃已经广泛应用于挡风玻璃的车辆。[86]自中世纪以来,眼镜就一直使用光学玻璃。[87]透镜的生产变得越来越熟练,有助于天文学家[88]以及在医学和科学中具有其他应用。[89]玻璃也用作许多太阳能收集器的孔径盖。[90]

从19世纪开始,许多古老的玻璃制造技术开始复兴,包括浮雕玻璃,自罗马帝国以来首次实现,最初主要用于新古典主义风格。[91]新艺术运动大量使用玻璃,[92]随着勒内·莱俪,艾米里·加利和南希的道明生产彩色花瓶和类似的产品,通常是浮雕玻璃,也使用光泽技术。路易斯·康福特·蒂芙尼在美国专门研究世俗和宗教的彩色玻璃,以及著名的灯具。20世纪初,诸如沃特福德和莱俪等公司大规模生产玻璃艺术品。大约从1960年开始,越来越多的小工作室手工制作玻璃艺术品,玻璃艺术家开始把自己归类为实际上在玻璃领域工作的雕塑家,他们的作品也是其中的一部分精细工艺。

在21世纪,科学家观察到古代彩色玻璃窗的特性,其中悬浮的纳米粒子阻止紫外线引起改变图像颜色的化学反应,正在开发摄像技术,使用类似彩色玻璃捕捉2019年火星的真实彩色图像欧空局火星车任务。[93]

4.1 建筑玻璃进步年表

- 1226:“宽板,首次生产于苏塞克斯。[94]

- 1330: 用于首次在法国鲁昂首次生产用于艺术品和船舶的“皇冠玻璃”。[95]“宽表”也产生了。两者都是出口供应的。

- 1500年代:一种用平板玻璃制作镜子的方法是由穆拉诺岛上的威尼斯玻璃制造商开发的,他们用汞-锡汞合金覆盖玻璃背面,获得近乎完美和无失真的反射。

- 17世纪20年代:“吹制板”首次在伦敦生产。[94]用于镜子和长途汽车牌照。[96]

- 1678年:“皇冠玻璃”首次在伦敦生产。[97]这个过程一直持续到19世纪。

- 1843年:由亨利·贝塞麦发明的早期形式的“浮法玻璃”,将玻璃倒在液体锡上。其昂贵而非商业成功。

- 1874年:钢化玻璃是由法国巴黎的弗朗索瓦·巴塞莱米·阿尔弗雷德·罗亚尔(1830-1901)通过在油浴或油脂浴中淬火几乎熔化的玻璃而开发的。

- 1888年:引入机器轧制玻璃,允许图案。[98]

- 1898年:皮尔金顿首次商业化生产的金属丝浇铸玻璃[99]用于安全或安保问题。[100]

- 1959年:浮法玻璃在英国推出。由阿拉斯泰尔·皮尔金顿爵士发明。[101][102]

瑞典科斯塔·格拉斯布鲁克(Kosta Glasbruk)的口吹玻璃,(1742年)上有吹玻璃工人管道上的浮子标记

英国坎特伯雷的一座建筑,它以不同的建筑风格和玻璃幕墙展示了其悠久的历史,包括从16世纪到20世纪的每一个世纪。

圣丹尼斯大教堂唱诗班的窗户,是最早使用大面积玻璃的地方之一。(13世纪早期的建筑,19世纪修复了的玻璃)

“哈德威克大厅,玻璃比墙还多。”(16世纪)

维也纳奥斯特赖希什邮局的窗户(20世纪初)

洛杉矶Westin Bonaventure酒店展示了玻璃作为建筑材料在20 - 21世纪的广泛使用

5 其他类型编辑

新的化学玻璃成分或新的处理技术可以在小规模实验室实验中进行初步研究。实验室规模玻璃熔体的原材料通常不同于大规模生产中使用的原材料,因为成本因素的优先级较低。在实验室中,大多使用纯化学品。必须注意原材料没有与环境中的水分或其他化学物质(如碱金属或碱土金属氧化物和氢氧化物或氧化硼)反应,或者杂质是定量的(烧失量)。[103]在选择原料时应考虑玻璃熔化过程中的蒸发损失,例如,亚硒酸钠可能优于容易蒸发的物质SeO2。此外,与相对惰性的原料相比,更容易反应的原料可能是优选的,例如Al(OH)3超过Al2O3。通常,熔化在铂坩埚中进行,以减少坩埚材料的污染。玻璃的均匀性是通过均化原料混合物(玻璃配合料)、搅拌熔体以及粉碎和再熔化第一熔体来实现的。所获得的玻璃通常进行退火,以防止加工过程中破裂。[103][104]

为了从玻璃形成倾向差的材料制造玻璃,使用新技术来提高冷却速率或减少晶体成核触发。这些技术的例子包括气动悬浮(在熔体漂浮在气流上的同时冷却熔体)、喷溅淬火(在两个金属砧之间挤压熔体)和辊淬火(通过辊浇注熔体)。

5.1 玻璃纤维

玻璃纤维(也称为玻璃增强塑料[105][106])是种复合材料,由嵌入塑料树脂中的玻璃纤维(也称为玻璃纤维[107]或者玻璃褶边[108])组成。[109][110]它是通过熔化玻璃并将玻璃拉伸成纤维制成的。这些纤维一起被编织成布,然后放入塑料树脂中固化。[111]

玻璃纤维丝是通过拉挤成型工艺制成的,其中原料(沙、石灰石、高岭土、氟石、硬硼钙石、白云石和其他矿物质)在大炉子中熔化成液体,该液体通过非常小的孔(如果玻璃是电子玻璃,其直径为5-25微米,如果玻璃是s型玻璃,其直径9微米)挤出。[112]

玻璃纤维具有轻质和耐腐蚀的特性。[113][114]玻璃纤维也是一种很好的绝缘体,[115]允许它用于隔离建筑物。[116]大多数玻璃纤维不耐碱。[117]玻璃纤维还具有随着玻璃老化而变得更强的特性。[118]

5.2 网络眼镜

不包括二氧化硅作为主要成分的某些类型的玻璃可能具有物理化学性质,可用于它们在光纤和其他专门技术应用中的应用。[119]这些包括氟化物玻璃、铝酸盐和铝硅酸盐玻璃、磷酸盐玻璃、硼酸盐玻璃和硫族化物玻璃。

氧化物玻璃有三类组分:网络形成剂、中间体和改性剂。[120]网络形成物(硅、硼、锗)形成高度交联的化学键网络。根据玻璃的组成,中间体(钛、铝、锆、铍、镁、锌)可以同时作为网络形成剂和改性剂。[121]改性剂(钙、铅、锂、钠、钾)改变网络结构;它们通常以离子的形式存在,由附近的非桥氧原子补偿,通过一个共价键结合到玻璃网络上,并保持一个负电荷以补偿附近的正离子。[122]有些元素可以扮演多重角色;例如,铅既可以作为网络形成剂(Pb4+替换Si4+)或作为修饰剂。[123]

非桥氧的存在降低了材料中强键的相对数并破坏了网络,降低了熔体的粘度并降低了熔化温度。[121]

碱金属离子小且可移动;它们在玻璃中的存在允许一定程度的电导率,特别是在熔融状态或高温下。它们的流动性降低了玻璃的耐化学性,允许水浸出并促进腐蚀。碱土金属离子带有两个正电荷,需要两个非桥氧离子来补偿它们的电荷,它们本身的移动性小得多,也阻碍其他离子,特别是碱金属的扩散。最常见的商用玻璃类型包含碱金属和碱土金属离子(通常是钠和钙),以便于加工和满足耐腐蚀性要求。[124]通过脱碱,通过与硫或氟化合物反应从玻璃表面去除碱金属离子,可以增加玻璃的耐腐蚀性。[125][126]碱金属离子的存在也会对玻璃的损耗角正切和它的电阻有不利影响。[127]为电子产品(密封、真空管、灯)制造的玻璃必须考虑到这一点。

氧化铅的加入降低熔点,降低熔体的粘度增加折射率。氧化铅也有助于其他金属氧化物的溶解,并用于有色玻璃。铅玻璃熔体的粘度下降非常显著(大约是苏打玻璃的100倍);这允许更容易地去除气泡和在并低温度下工作,因此它经常被用作搪瓷和璃焊料中的添加剂。高离子半径的Pb2+离子使其在基质中高度不动,并阻碍其他离子的移动;铅玻璃因此具有高电阻,比钠钙玻璃(108.5vs 106.5 ω⋅cm特区,250℃)。[128]

添加氟降低玻璃的介电常数。氟带高负电的并且吸引晶格中的电子,降低材料的极化率。这种二氧化硅-氟化物用于制造集成电路的绝缘体。高含量氟掺杂导致挥发性SiF2O的形成,种玻璃是热不稳定的。介当介电常数低至约3.5–3.7时,稳定层得以实现。[129]

5.3 无定形金属

过去,小批量的具有高表面积结构的非晶体金属(带、线、膜等)是通过实现极快的冷却速度而产生的。加州理工学院的博士生W. Klement最初将这种现象称为“splat cooling”,他指出每秒几百万度的冷却速度足以阻止晶体的形成,金属原子会“锁定”在玻璃态。非晶态金属线是通过将熔融金属溅射到旋转的金属盘上生产的。最近,已经生产出许多厚度超过1微米的合金。这些被称为大块金属玻璃(BMG)。液态金属技术公司销售多种锆基BMG。还生产了成批的非晶钢,这些非晶钢的机械性能远远超过了传统钢合金的机械性能。[130][131][132]

2004年,NIST 研究人员提出证据表明,可以从熔体中生长出各向同性的非晶态金属相(称为“q-玻璃”)。这一相是快速冷却过程中在铝-铁-硅系统中形成的第一相,或“初级相”。实验证据表明,这个相是由一个一级相变。透射电子显微镜图像显示,q-玻璃从熔体中成核为离散粒子,以均匀的生长速率在所有方向上球形生长。衍射图显示它是各向同性玻璃相。然而存在成核障碍,这意味着玻璃和熔体之间的界面(或内表面)不连续性。[133][134]

5.4 电解质

电解质或熔融盐是不同离子的混合物。在三种或更多种不同尺寸和形状的离子物质的混合物中,结晶可能非常困难,以至于液体可以容易地过冷成玻璃。研究得最好的例子是Ca0.4K0.6(NO3)1.4。钡掺杂的锂-玻璃和钡掺杂的钠-玻璃形式的玻璃电解质已经被提出作为现代锂离子电池单元中使用的有机液体电解质的问题的解决方案。[135]

5.5 水溶液

一些水溶液可以过冷成玻璃态,[136][137]例如LiCl:RH2O(氯化锂盐和水分子的溶液),组成范围4<R< 8。[138]含糖的水溶液具有玻璃态,可用作表面活性剂。[139]

5.6 分子液体

分子液体由不形成共价网络但仅通过弱范德华力或通过瞬态氢键相互作用的分子组成。许多分子液体可以过冷成玻璃;有些是通常不结晶的优质形成剂。

这方面的一个例子是糖玻璃。[140]

在极端压力和温度下,固体可能表现出大的结构和物理变化,这可能导致多晶相变。[141]2006年,意大利科学家利用极端压力创造了一种无定形的二氧化碳。这种物质被命名为无定形碳(α-CO2)并表现出类似二氧化硅的原子结构。[142]

5.7 聚合物

重要的聚合物玻璃包括无定形和玻璃态药物化合物。这些是有用的,因为与相同的结晶组合物相比,当化合物为无定形时,其溶解度大大增加。许多新兴药物在其结晶态实际上不溶的。[143]

5.8 胶体玻璃

浓缩的胶体悬浮液可以表现出与颗粒浓度或密度相关的明显的玻璃化转变。[144][145][146]

在细胞生物学中,最近的证据表明细胞质的行为像一个胶体玻璃,接近液-玻璃转化。[147][148]在低代谢活动期间,如在休眠中,细胞质玻璃化并阻止向较大细胞质颗粒的移动,同时允许较小的颗粒在整个细胞中扩散。[147]

5.9 玻璃陶瓷

玻璃陶瓷材料与非晶态玻璃和晶态陶瓷具有许多共同的特性 。它们形成玻璃,然后通过热处理部分结晶。例如,白色陶瓷的微观结构通常包含无定形相和结晶相。晶粒通常嵌在晶界的晶态的晶粒间相中。当应用于白色陶瓷时,玻璃质意味着该材料对液体具有极低的渗透性,当由特定的试验方案测定时,通常但不总是水。[149][150]

该术语主要指锂和铝硅酸盐的混合物,其产生具有令人感兴趣的热机械性能的一系列材料。其中最重要的商业特性是耐热冲击。因此,玻璃陶瓷已经变得非常适用于台面烹饪。结晶陶瓷相的负热膨胀系数(CTE)可以与玻璃相的正CTE相平衡。在某一点上(约70%结晶),玻璃陶瓷的净CTE接近于零。这种类型的玻璃陶瓷表现出优异的机械性能,可承受高达1000°C的反复和快速温度变化。[149][150]

6 结构编辑

和其他无定形固体一样,玻璃的原子结构缺乏在结晶固体中观察到的长程周期性。由于化学键合特性,玻璃确实具有相对于局部原子多面体的高度短程有序性。[151]

6.1 液体过冷的形成

在物理学中,玻璃(或玻璃固体)的标准定义是通过快速熔融淬火形成的固体,[152][153][154][155][156]尽管术语玻璃通常用于描述任何表现出玻璃化转变温度Tg的无定形固体。对于熔融淬火,如果冷却足够快(相对于特征结晶时间),则结晶被阻止,相反,过冷液体的无序原子构型在温度Tg下冻结成固态。材料淬火时形成玻璃趋势称为玻璃形成能力。这种能力可以通过刚性理论来预测。[157]通常,相对于其结晶形式,玻璃以结构上的亚稳态存在,尽管在某些情况下,例如在无规立构聚合物中,没有无定形相的结晶类似物。[158]

玻璃由于缺乏一级相变,有时被认为是液体,[159][160]其中某些热力学变量如体积、熵和焓在整个玻璃化转变范围内是不连续的。玻璃化转变可以被描述为类似于二阶相变,其中强热力学变量如热膨胀系数和热容量是不连续的。[153]然而,相变的平衡理论并不完全适用于玻璃,因此玻璃化转变不能被归类为固体中经典的平衡相变之一。[155][156]

玻璃是无定形固体。它具有在与在液液种体过冷相观察到的原子结构,但显示出固体的所有机械性质。[159][161]经验研究或理论分析并不支持玻璃长时间流动到可感知程度的观点。室温玻璃流的实验室测量确实显示了与1017–1018Pa s量级的材料粘度一致的运动 。[162]

尽管玻璃的原子结构与液体过冷玻璃的结构具有相同的特征,但玻璃在其玻璃化转变温度以下倾向于表现为固体。[163]液体过冷表现得像一种液体,但低于它的冰点,在某些情况下,如果加入晶体作为核心,晶体将几乎立即结晶。玻璃化转变时热容量的变化和具有可比性的材料的熔化转变通常具有相同的数量级,表明活性的变化自由度也是可比的。无论是在玻璃里还是在水晶里,它大多只是震动保持活动的所有自由度,而旋转和平移的运动被阻止。这有助于解释为什么晶体和非晶体固体在大多数实验时间尺度上都表现出刚性。

6.2 仿古玻璃的行为

有时发现旧窗户在底部比在顶部更厚的观察结果通常被认为是玻璃在几个世纪的时间范围内流动的观点的支持证据,假设玻璃具有流动的液体特性,即一种形状到另一种形状。[164]这种假设是不正确的,因为一旦凝固,玻璃就会停止流动。观察的原因是,在过去,当窗玻璃通常由玻璃鼓风机制成时,技术是旋转熔融玻璃,以创造一个圆形,大部分是平的,甚且均匀的he冠状玻璃工艺所述)。然后把这个盘子切板合窗户的形状。这些碎片不是绝对平坦的;随着玻璃的旋转,圆盘的边缘变得不同成度。当安装在窗框中时,为了稳定和防止水在引线中窗户底部聚铅的,玻璃将较厚的一侧朝下放置来在窗户的底部。[165]偶尔,这种玻璃较厚的一侧被发现安装在顶部、左侧或右侧。[166]

二十世纪初玻璃窗玻璃的大规模生产也产生了类似的效果。在玻璃工厂,将熔融玻璃倒在大型冷却台上并使其展开。得到的玻璃在浇注位置较厚,位于大玻璃板的中心。这些板材被切割成厚度不均匀的较小窗玻璃,通常浇注位置居中于其中一个窗格(称为“靶心”)以达到装饰效果。用于窗户的现代玻璃生产为浮法玻璃,厚度非常均匀。

可以被认为与“教堂玻璃流”理论相矛盾的其他几个点:

- 材料工程师Edgar D. Zanotto在美国物理杂志写道”...GeO2在室温下预测的弛豫时间为1032年。因此,大教堂玻璃的松弛期(特征流动时间)会更长。"[167](1032年比估计的宇宙年龄长很多倍。)

- 如果中世纪的玻璃明显的流动,那么古罗马和埃及的物体应该流动得更成比例——但这没有被观察到。同样,史前黑曜石刀片应该已经失去了边缘;这也没有观察到(尽管黑曜石可能与窗玻璃具有不同的粘度)。[159]

- 如果玻璃流动的速度允许几个世纪后用肉眼看到变化,那么这种效应在古董中的望远镜应该是显而易见。古董望远镜镜头的任何轻微变形都会导致光学性能显著下降,这是一种尚未观察到的现象。然而,望远镜透镜中使用的玻璃通常不同于窗玻璃中使用的玻璃。[159]

7 画廊编辑

耳钉,约公元前1390-1353年,48.66.30,布鲁克林博物馆。这些色彩鲜艳的耳钉的轴通过耳垂上的一个孔插入,以显示耳钉的圆形头部。

公元前5 - 6世纪 腓尼基玻璃项链

公元 1-2世纪 罗马玻璃

蓝头烧瓶(罗马,公元300-500年,铸玻璃)

伦巴第酒杯饮用角 6 - 7世纪

约1700-1775年,印度莫卧儿邦,两杯钴蓝色玻璃,饰以镀金的花卉装饰

水管基地,印度,莫卧儿,约1700-1775年

威尼斯高脚杯产于19世纪初的意大利

孔雀手镯,德里,镶嵌宝石和玻璃的珐琅银手镯,19世纪

朱尔,1876年,詹姆斯·鲍威尔父子公司

虹吸管瓶装苏打水,1922年

新马丁斯维尔玻璃主人茶杯,钴蓝色,1930年

香水,来自苏联,大约1965年

玻璃花瓶

窗玻璃

玻璃枝形吊灯上的细节

玻璃吊灯

维多利亚和阿尔伯特博物馆(Victoria and Albert Museum)的圆形大厅,也就是正门,现在挂着一盏30英尺高的戴尔·奇胡利(Dale Chihuly)吹制玻璃枝形吊灯

道光时期北京玻璃花瓶。这种颜色以清朝的国旗命名为“皇黄色”

在这款“神秘手表”中,玻璃表盘的使用制造了一种手不动的错觉

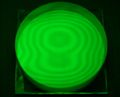

用光学平板测试平面度。光滑的玻璃表面被用来测量比光波长小得多的光和暗条纹。

铀玻璃蛋糕架在紫外线下发出荧光

现代玻璃可以被凿成不朽的雕塑形式

参考文献

- [1]

^Lewis, Peter Rhys (9 June 2016). Forensic Polymer Engineering: Why Polymer Products Fail in Service. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-100728-0. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [2]

^Klein, Hermann Joseph (1 January 1881). Land, sea and sky; or, Wonders of life and nature, tr. from the Germ. [Die Erde und ihr organisches Leben] of H.J. Klein and dr. Thomé, by J. Minshull. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [3]

^"Glass – Chemistry Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015..

- [4]

^"Borosilicate Glass vs. Soda Lime Glass?". rayotek.com. 2 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017..

- [5]

^Robertson, Gordon L. (2005). Food Packaging: Principles and Practice (Second ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-3775-8. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [6]

^"Glass Ingredients – What is Glass Made Of?". www.historyofglass.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017..

- [7]

^Pfaender, Heinz G. (1996). Schott guide to glass. Springer. pp. 135, 186. ISBN 978-0-412-62060-7. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2011..

- [8]

^Chawla, Sohan L. (1993). Materials Selection for Corrosion Control. ASM International. ISBN 978-1-61503-728-5. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [9]

^Ashby, Michael F.; Johnson, Kara (2013). Materials and Design: The Art and Science of Material Selection in Product Design. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-098282-3. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [10]

^开采海沙 Archived 29 2月 2012 at the Wayback Machine。Seafriends.org.nz(1994-02-08)。检索于2012-05-15。.

- [11]

^Punmia, Dr B.C.; Jain, Ashok Kumar; Jain, Arun Kr (2003). Basic Civil Engineering. Firewall Media. ISBN 978-81-7008-403-7. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [12]

^Nema, Sandeep; Ludwig, John D. (2010). Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms – Parenteral Medications, Third Edition: Volume 3: Regulations, Validation and the Future. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-8648-5. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [13]

^Khatib, Jamal (2016). Sustainability of Construction Materials. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-100391-6. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [14]

^Jr, Robert H. Hill; Finster, David C. (2016). Laboratory Safety for Chemistry Students. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-24338-0. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [15]

^Spence, William P.; Kultermann, Eva (2016). Construction Materials, Methods and Techniques. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-305-08627-2. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [16]

^Tilstone, William J.; Savage, Kathleen A.; Clark, Leigh A. (2006). Forensic Science: An Encyclopedia of History, Methods, and Techniques. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-194-6. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [17]

^Worrell, Ernst; Reuter, Markus (2014). Handbook of Recycling: State-of-the-art for Practitioners, Analysts, and Scientists. Newnes. ISBN 978-0-12-396506-6. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [18]

^康宁公司派热克斯数据表 Archived 13 1月 2012 at the Wayback Machine。(PDF)。检索于2012-05-15。.

- [19]

^阿尔-GLAS Archived 12 6月 2012 at the Wayback Machine纽约斯科特公司数据表.

- [20]

^Ericsson, Anne-Marie (1996). The Brilliance of Swedish Glass, 1918–1939: An Alliance of Art and Industry. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07005-7..

- [21]

^Schwartz, Mel (2002). Encyclopedia of Materials, Parts and Finishes (Second ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-1716-8. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [22]

^Shelby, J.E. (2017). Introduction to Glass Science and Technology. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-85404-639-3. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [23]

^Askeland, Donald R.; Fulay, Pradeep P. (2008). Essentials of Materials Science & Engineering. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-24446-2. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017..

- [24]

^Bradford, S. (2012). Corrosion Control. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4684-8845-6..

- [25]

^Jiang, Xin; Lousteau, Joris; Richards, Billy; Jha, Animesh (2009-09-01). "Investigation on germanium oxide-based glasses for infrared optical fibre development". Optical Materials. 31 (11): 1701–1706. Bibcode:2009OptMa..31.1701J. doi:10.1016/j.optmat.2009.04.011..

- [26]

^Mukherjee, Swapna (2013). The Science of Clays: Applications in Industry, Engineering, and Environment. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-007-6683-9..

- [27]

^Barsoum, Michel W. (2003). Fundamentals of ceramics (2 ed.). Bristol: IOP. ISBN 978-0-7503-0902-8..

- [28]

^Donald R. Uhlmann; Norbert J. Kreidl, eds. (1991). Optical properties of glass. Westerville, OH: American Ceramic Society. ISBN 978-0-944904-35-0..

- [29]

^Lyle, D. P. (2008). Howdunit Forensics. Writer's Digest Books. ISBN 978-1-58297-474-3..

- [30]

^Khatib, Jamal (2016-08-12). Sustainability of Construction Materials. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-100391-6..

- [31]

^Ramakrishna, A. (2014). Goyal's I I T Foundation Course Chemistry: For Class- 7. Goyal Brothers Prakashan..

- [32]

^Apodaca, Anthony A.; Gritz, Larry; Barzel, Ronen (2000). Advanced RenderMan: Creating CGI for Motion Pictures. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-1-55860-618-0..

- [33]

^White, Mary Anne (2011). Physical Properties of Materials, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-9532-0..

- [34]

^Grattan, L.S.; Meggitt, B.T. (2013). Optical Fiber Sensor Technology: Advanced Applications – Bragg Gratings and Distributed Sensors. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4757-6079-8..

- [35]

^Terzis, Anestis (2016). Handbook of Camera Monitor Systems: The Automotive Mirror-Replacement Technology based on ISO 16505. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-29611-1..

- [36]

^Khatib, Jamal (2016). Sustainability of Construction Materials. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-100391-6..

- [37]

^Kasap, Safa; Ruda, Harry; Boucher, Yann (2009). Cambridge Illustrated Handbook of Optoelectronics and Photonics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-64372-6..

- [38]

^Jelínková, Helena (2013). Lasers for Medical Applications: Diagnostics, Therapy and Surgery. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-85709-754-5..

- [39]

^Mattox, D.M. (2014). Handbook of Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) Processing. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-08-094658-0..

- [40]

^Zarzycki, Jerzy (1991). Glasses and the Vitreous State. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35582-7..

- [41]

^Tilstone, William J.; Savage, Kathleen A.; Clark, Leigh A. (2006). Forensic Science: An Encyclopedia of History, Methods, and Techniques. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-194-6..

- [42]

^Simmons, H. Leslie (2011). Olin's Construction: Principles, Materials, and Methods. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-06705-5..

- [43]

^Oxley, John (1994). Stained glass in South Africa. William Waterman Publications. ISBN 978-1-874959-09-0..

- [44]

^Ward-Harvey, K. (2009). Fundamental Building Materials. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59942-954-0..

- [45]

^Gardner, Irvine Clifton; Hahner, Clarence H. (1949). Research and Development in Applied Optics and Optical Glass at the National Bureau of Standards: A Review and Bibliography. U.S. Government Printing Office..

- [46]

^Dudeja, Puja; Gupta, Rajul K.; Minhas, Amarjeet Singh (2016). Food Safety in the 21st Century: Public Health Perspective. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-801846-0..

- [47]

^Aulton, Michael E.; Taylor, Kevin (2013). Aulton's Pharmaceutics: The Design and Manufacture of Medicines. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-7020-4290-4..

- [48]

^Bengisu, M. (2013). Engineering Ceramics. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-04350-9..

- [49]

^Batchelor, Andrew W.; Loh, Nee Lam; Chandrasekaran, Margam (2011). Materials Degradation and Its Control by Surface Engineering. World Scientific. ISBN 978-1-908978-14-1..

- [50]

^Chawla, Sohan L. (1993). Materials Selection for Corrosion Control. ASM International. ISBN 978-1-61503-728-5..

- [51]

^Technomic (1998). SPI/CI International Conference and Exposition 1998. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-56676-642-5..

- [52]

^Kasunic, Keith J. (2015). Optomechanical Systems Engineering. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-80990-7..

- [53]

^Lehman, Richard (24 November 2017). "The Mechanical Properties of Glass" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017..

- [54]

^The Glass Industry. Ashlee Publishing Company, Incorporated. 1923..

- [55]

^"Glass Strength". www.pilkington.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017..

- [56]

^B.H.W.S. de Jong,"玻璃";在《乌尔曼反应工业化学百科全书》中;第五版,A12卷,VCH出版社,韦因海姆,德国,1989年,ISBN 978-3-527-20112-9,第365-432页。.

- [57]

^Office, U.S. Government Printing (October 2011). Code of Federal Regulations, Title 40,: Protection of Environment, Part 60 (Sections 60.1-end), Revised As of July 1, 2011. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-088907-3..

- [58]

^Richling, Jeffrey (2017). Scratching the Surface – An Introduction to Photonics – Part 1 Optics, Thin Films, Lasers and Crystals. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-312-65170-8..

- [59]

^"windshields how they are made". autoglassguru. Retrieved 2018-02-09..

- [60]

^Pantano, Carlo. "Glass Surface Treatments: Commercial Processes Used in Glass Manufacture" (PDF)..

- [61]

^Vogel, Werner (1994). Glass Chemistry (2 ed.). Springer-Verlag Berlin and Heidelberg GmbH & Co. K. ISBN 978-3-540-57572-6..

- [62]

^Thomas P. Seward, ed. (2005). High temperature glass melt property database for process modeling. Westerville, Ohio: American Ceramic Society. ISBN 978-1-57498-225-1..

- [63]

^大卫·伊西特。用于制造彩色玻璃的物质1st.glassman.com。.

- [64]

^Shelby, James E. (2007). Introduction to Glass Science and Technology. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84755-116-0..

- [65]

^"Glass Online: The History of Glass". Archived from the original on 24 October 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2007..

- [66]

^直到第一种玻璃生产后的许多世纪,才在陶瓷体上使用真正的玻璃。.

- [67]

^Gowlett, J.A.J. (1997). High Definition Archaeology: Threads Through the Past. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-18429-8. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017..

- [68]

^Douglas, R.W. (1972). A history of glassmaking. Henley-on-Thames: G T Foulis & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85429-117-5..

- [69]

^Whitehouse, David; Glass, Corning Museum of (2003). Roman Glass in the Corning Museum of Glass. Hudson Hills. ISBN 978-0-87290-155-1. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [70]

^The Art Journal. Virtue and Company. 1888..

- [71]

^The Glass Industry. Ashlee Publishing Company. 1920..

- [72]

^Dien, Albert E. (2007). Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [73]

^Silberman, Neil Asher; Bauer, Alexander A. (2012). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [74]

^Stachurski, Zbigniew H. (2015). Fundamentals of Amorphous Solids: Structure and Properties. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-68219-5..

- [75]

^Walford, Edward; Apperson, George Latimer (1887). The Antiquary: A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past. E. Stock..

- [76]

^Keller, Daniel; Price, Jennifer; Jackson, Caroline (2014). Neighbours and Successors of Rome: Traditions of Glass Production and use in Europe and the Middle East in the Later 1st Millennium AD. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78297-398-0..

- [77]

^Churchill, Lady Randolph Spencer (1900). The Anglo-Saxon Review. John Lane..

- [78]

^Rene Hughe,拜占庭和欧洲中世纪美术保罗·哈姆林(1963).

- [79]

^约翰·哈维,英国教堂巴特福德,(1961).

- [80]

^Packard, Robert T.; Korab, Balthazar; Hunt, William Dudley (1980). Encyclopedia of American architecture. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-048010-0..

- [81]

^Tutag, Nola Huse; Hamilton, Lucy (1987). Discovering Stained Glass in Detroit. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1875-1. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017..

- [82]

^Brown, Sarah; O'Connor, David (1991). Glass-painters. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6917-7..

- [83]

^The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1983. ISBN 978-0-85229-400-0..

- [84]

^Freiman, Stephen (2007). Global Roadmap for Ceramic and Glass Technology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-10491-0..

- [85]

^Gelfand, Lisa; Duncan, Chris (2011). Sustainable Renovation: Strategies for Commercial Building Systems and Envelope. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-10217-6..

- [86]

^Lim, Henry W.; Honigsmann, Herbert; Hawk, John L.M. (2007). Photodermatology. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-1996-4..

- [87]

^Bach, Hans; Neuroth, Norbert (2012). The Properties of Optical Glass. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-57769-7..

- [88]

^McLean, Ian S. (2008). Electronic Imaging in Astronomy: Detectors and Instrumentation. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-76582-0 – via Google Books..

- [89]

^Meyers, Morton A. (2011). Happy Accidents: Serendipity in Major Medical Breakthroughs in the Twentieth Century. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61145-162-7..

- [90]

^Enteria, Napoleon; Akbarzadeh, Aliakbar (2013). Solar Energy Sciences and Engineering Applications. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-76205-9..

- [91]

^Miller, Judith (2006). Decorative Arts. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7566-2349-4..

- [92]

^Cresswell, Lesley (2004). Graphic with Materials Technology. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-75768-7..

- [93]

^Zolfagharifard, Ellie (15 October 2013). "How medieval stained-glass is creating the ultimate SPACE camera: Nanoparticles used in church windows will help scientists see Mars' true colours under extreme UV light". Daily Mail. London. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013..

- [94]

^Ginn, Peter; Goodman, Ruth (2013). Tudor Monastery Farm: Life in rural England 500 years ago. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-4172-2..

- [95]

^Bridgwood, Barry; Lennie, Lindsay (2013). History, Performance and Conservation. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-134-07899-8..

- [96]

^Silliman, Benjamin; Goodrich, Charles Rush (1854). The World of Science, Art, and Industry: Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54. G.P. Putnam..

- [97]

^Mooney, Barbara Burlison (2008). Prodigy Houses of Virginia: Architecture and the Native Elite. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-2673-5..

- [98]

^Forsyth, Michael (2013). Materials and Skills for Historic Building Conservation. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-65866-6..

- [99]

^Practical Building Conservation: Glass and glazing. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. 2011. ISBN 978-0-7546-4557-3..

- [100]

^McNeill, John; Pomeranz, Kenneth (2015). The Cambridge World History: Volume 7, Production, Destruction and Connection, 1750–Present, Part 1, Structures, Spaces, and Boundary Making. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-29812-1..

- [101]

^玻璃制造历史:伦敦冕玻璃公司.

- [102]

^Notes on Science and Technology in Britain. The Office. April 1967..

- [103]

^"Glass melting, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory". Depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2009..

- [104]

^Fluegel, Alexander. "Glass melting in the laboratory". Glassproperties.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009..

- [105]

^Woodhouse, Philip (2013). Sea Kayaking: A Guide for Sea Canoeists. Balboa Press. ISBN 978-1-4525-0849-8. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017..

- [106]

^Burrill, Daniel; Zurschmeide, Jeffery (2012). How to Fabricate Automotive Fiberglass & Carbon Fiber Parts. CarTech Inc. ISBN 978-1-934709-98-6..

- [107]

^Bradt, R. C.; Tressler, R.E. (2013). Fractography of Glass. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4899-1325-8..

- [108]

^Bryce, Douglas M. (1997). Plastic Injection Molding: Material Selection and Product Design Fundamentals. Society of Manufacturing Engineers. ISBN 978-0-87263-488-6..

- [109]

^Kamen, Gary (2001). Foundations of Exercise Science. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-04498-0. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [110]

^The Complete Guide to Auto Body Repair. MotorBooks International. ISBN 978-1-61059-206-2. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017..

- [111]

^"Properties of Matter Reading Selection: Perfect Teamwork". www.propertiesofmatter.si.edu. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2017..

- [112]

^Bhatnagar, Ashok (2016). Lightweight Ballistic Composites: Military and Law-Enforcement Applications. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-100425-8..

- [113]

^Certain Steel Grating from China, Invs. 701-TA-465 and 731-TA-1161 (Preliminary). DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4578-1677-2. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017..

- [114]

^"Fiberglass and Composite Material Design Guide". www.performancecomposites.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2017..

- [115]

^Jain, Ravi; Lee, Luke (2012). Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Composites for Infrastructure Applications: Focusing on Innovation, Technology Implementation and Sustainability. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-007-2356-6..

- [116]

^Kaviany, Massoud (2002). Principles of Heat Transfer. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-43463-4..

- [117]

^Kogel, Jessica Elzea (2006). Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses. SME. ISBN 978-0-87335-233-8..

- [118]

^Canning, Captain Wayne (2017). Fiberglass Boat Restoration: The Project Planning Guide. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-944824-27-3..

- [119]

^Rivera, V. A. G.; Manzani, Danilo (2017). Technological Advances in Tellurite Glasses: Properties, Processing, and Applications. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-53038-3..

- [120]

^Karmakar, Basudeb; Rademann, Klaus; Stepanov, Andrey (2016). Glass Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. William Andrew. ISBN 978-0-323-39312-6..

- [121]

^Stolten, Detlef; Emonts, Bernd (2012). Fuel Cell Science and Engineering: Materials, Processes, Systems and Technology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-65026-2..

- [122]

^Bernhard, Kienzler; Marcus, Altmaier; Christiane, Bube; Volker, Metz (2012). Radionuclide Source Term for HLW Glass, Spent Nuclear Fuel, and Compacted Hulls and End Pieces (CSD-C Waste). KIT Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-3-86644-907-7..

- [123]

^Zhu, Yuntian. "MSE200 Lecture 19 (CH. 11.6, 11.8) Ceramics" (PDF). Retrieved October 15, 2017..

- [124]

^Bourhis, Eric Le (2007). Glass: Mechanics and Technology. Wiley-VCH. p. 74. ISBN 978-3-527-31549-9. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017..

- [125]

^Baldwin, Charles; Evele, Holger; Pershinsky, Renee (2010). Advances in Porcelain Enamel Technology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-64089-0..

- [126]

^Day, D.E. (2013). Glass Surfaces: Proceedings of the Fourth Rolla Ceramic Materials Conference on Glass Surfaces, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 15–19 June, 1975. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-6522-6..

- [127]

^Electri-onics. Lake Publishing Corporation. 1985..

- [128]

^Shackelford, James F.; Doremus, Robert H. (2008). Ceramic and Glass Materials: Structure, Properties and Processing. Springer. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-387-73361-6. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017..

- [129]

^Doering, Robert; Nishi, Yoshio (2007). Handbook of semiconductor manufacturing technology. CRC Press. pp. 12–3. ISBN 978-1-57444-675-3. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017..

- [130]

^Klement, Jr., W.; Willens, R.H.; Duwez, Pol (1960). "Non-crystalline Structure in Solidified Gold-Silicon Alloys". Nature. 187 (4740): 869. Bibcode:1960Natur.187..869K. doi:10.1038/187869b0..

- [131]

^Liebermann, H.; Graham, C. (1976). "Production of Amorphous Alloy Ribbons and Effects of Apparatus Parameters on Ribbon Dimensions". IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 12 (6): 921. Bibcode:1976ITM....12..921L. doi:10.1109/TMAG.1976.1059201..

- [132]

^Ponnambalam, V.; Poon, S. Joseph; Shiflet, Gary J. (2004). "Fe-based bulk metallic glasses with diameter thickness larger than one centimeter". Journal of Materials Research. 19 (5): 1320. Bibcode:2004JMatR..19.1320P. doi:10.1557/JMR.2004.0176..

- [133]

^"Metallurgy Division Publications". NIST Interagency Report 7127. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008..

- [134]

^Mendelev, M.I.; Schmalian, J.; Wang, C.Z.; Morris, J.R.; K.M. Ho (2006). "Interface Mobility and the Liquid-Glass Transition in a One-Component System". Physical Review B. 74 (10): 104206. Bibcode:2006PhRvB..74j4206M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.74.104206..

- [135]

^"Lithium-Ion Pioneer Introduces New Battery That's Three Times Better". Fortune. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017..

- [136]

^Gruverman, Irwin J. (2013). Mössbauer Effect Methodology: Volume 6 Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium on Mössbauer Effect Methodology New York City, January 25, 1970. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4684-3159-9..

- [137]

^Levine, Harry; Slade, Louise (2013). Water Relationships in Foods: Advances in the 1980s and Trends for the 1990s. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4899-0664-9..

- [138]

^J., Dupuy; J., Jal; B., Prével; A., Aouizerat-Elarby; P., Chieux; J., Dianoux, A.; J., Legrand (1992). "Vibrational dynamics and structural relaxation in aqueous electrolyte solutions in the liquid, undercooled liquid and glassy states". Archived from the original on 11 October 2017..

- [139]

^Ogawa, Shigesaburo; Osanai, Shuichi. "Glass Behavior of Aqueous solution of Sugar Based Surfactants" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017..

- [140]

^Hartel, Richard W.; Hartel, AnnaKate (2014). Candy Bites: The Science of Sweets. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4614-9383-9..

- [141]

^McMillan, P.F. (2004). "Polyamorphic Transformations in Liquids and Glasses". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 14 (10): 1506–1512. doi:10.1039/b401308p..

- [142]

^实验室制造的二氧化碳玻璃 Archived 1 5月 2015 at the Wayback Machine。新闻科学家。2006年6月15日。.

- [143]

^了解聚合物玻璃 Archived 25 5月 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- [144]

^Pusey, P.N.; Megen, W. van (1987). "Observation of a glass transition in suspensions of spherical colloidal particles". Physical Review Letters. 59 (18): 2083–2086. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.2083P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.2083. PMID 10035413..

- [145]

^Megen, W. Van; Underwood, S. (1993). "Dynamic-light-scattering study of glasses of hard colloidal spheres". Physical Review E. 47 (1): 248. Bibcode:1993PhRvE..47..248V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.47.248..

- [146]

^Löwen, H. (1996). A.K. Arora; B.V.R. Tata, eds. "Dynamics of charged colloidal suspensions across the freezing and glass transition" (PDF). Ordering and Phase Transitions in Charged Colloids. VCH Series of Textbooks on "Complex Fluids and Fluid Microstructures": 207–234. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2013..

- [147]

^Parry, Bradley R.; Surovtsev, Ivan V.; Cabeen, Matthew T.; O’Hern, Corey S.; Dufresne, Eric R.; Jacobs-Wagner, Christine (2014). "The Bacterial Cytoplasm Has Glass-like Properties and Is Fluidized by Metabolic Activity". Cell (in English). 156 (1): 183–194. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.028. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 3956598. PMID 24361104.CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link).

- [148]

^Munguira, Ignacio (9 February 2016). "Glasslike Membrane Protein Diffusion in a Crowded Membrane" (PDF). ACS Nano. 10 (2): 2584–2590. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5b07595. PMID 26859708..

- [149]

^Kingery, W.D.; Uhlmann, H.K. Bowen, D.R. (1976). Introduction to ceramics (2 ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-47860-7..

- [150]

^Richerson, David W. (1992). Modern ceramic engineering : properties, processing and use in design (2 ed.). New York: Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-8634-2..

- [151]

^Salmon, P. S. (2002). "Order within disorder". Nature Materials. 1 (2): 87–8. doi:10.1038/nmat737. PMID 12618817..

- [152]

^ASTM 1945年对玻璃的定义;另外: DIN 1259,Glas–begriff für Glasarten und glasgrupen,1986年9月.

- [153]

^Zallen, R. (1983). The Physics of Amorphous Solids. New York: John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-01968-8..

- [154]

^Cusack, N.E. (1987). The physics of structurally disordered matter: an introduction. Adam Hilger in association with the University of Sussex press. ISBN 978-0-85274-829-9..

- [155]

^Elliot, S.R. (1984). Physics of Amorphous Materials. Longman group ltd..

- [156]

^Scholze, Horst (1991). Glass – Nature, Structure, and Properties. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-97396-8..

- [157]

^Phillips, J.C. (1979). "Topology of covalent non-crystalline solids I: Short-range order in chalcogenide alloys". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 34 (2): 153. Bibcode:1979JNCS...34..153P. doi:10.1016/0022-3093(79)90033-4..

- [158]

^Folmer, J.C.W.; Franzen, Stefan (2003). "Study of polymer glasses by modulated differential scanning calorimetry in the undergraduate physical chemistry laboratory". Journal of Chemical Education. 80 (7): 813. Bibcode:2003JChEd..80..813F. doi:10.1021/ed080p813..

- [159]

^Gibbs, Philip. "Is glass liquid or solid?". Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2007..

- [160]

^Loy, Jim. "Glass Is A Liquid?". Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2007..

- [161]

^“菲利普·吉布斯”玻璃世界,(2007年5月/6月),第14-18页.

- [162]

^Vannoni, M.; Sordini, A.; Molesini, G. (2011). "Relaxation time and viscosity of fused silica glass at room temperature". Eur. Phys. J. E. 34 (9): 9–14. doi:10.1140/epje/i2011-11092-9. PMID 21947892..

- [163]

^Neumann, Florin. "Glass: Liquid or Solid – Science vs. an Urban Legend". Archived from the original on 9 April 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007..

- [164]

^Kenneth Chang (29 July 2008). "The Nature of Glass Remains Anything but Clear". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2008..

- [165]

^"Dr Karl's Homework: Glass Flows". Australia: ABC. 26 January 2000. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009..

- [166]

^Halem, H. "Does Glass Flow". Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2010..

- [167]

^Zanotto, Edgar Dutra (1998). "Do Cathedral Glasses Flow?". American Journal of Physics. 66 (5): 392–396. Bibcode:1998AmJPh..66..392Z. doi:10.1119/1.19026..

暂无