ENIAC

编辑ENIAC(电子数字积分计算机)[1] 是第一台电子通用计算机。[2] 它是图灵完全和数字化的,能够通过重新编程解决“一大类数值问题”。[3][4]

虽然ENIAC是为美国陆军弹道研究实验室设计并主要用于计算火炮射表[5],但它的第一个项目是研究热核武器的可行性。[6][7]

ENIAC于1945年完工,并于1945年12月10日首次投入实用。[8]

ENIAC于1946年2月15日在宾夕法尼亚大学正式成立,并被媒体誉为“巨型大脑”。[9] 它的指令速度比机电机器快一千倍左右;这种计算能力,加上通用可编程能力,让科学家和实业家非常兴奋。速度和可编程能力的结合使得对问题进行成千上万次的计算变成现实,因为ENIAC在30秒内计算出的一条轨迹,需要耗费人类20个小时的计算(可用一个ENIAC小时取代2400个人工时)。[10] 完工的机器在1946年2月14日晚向公众公布,并于第二天在宾夕法尼亚大学正式投入使用,造价近50万美元(约为今天的630万美元)。它在1946年7月被美国陆军军械部正式接受。ENIAC于1946年11月9日因整修和内存升级而被关闭,并于1947年被转移到马里兰州阿伯丁试验场。在那里,它于1947年7月29日被启动并持续运行到1955年10月2日晚上11点45分。

目录编辑

1 开发和设计编辑

ENIAC的设计和建造由美国陆军、军械部、研究与发展司令部资助,由格雷顿·巴恩斯少将领导。总耗资约为487000美元,相当于2018年的7051000美元。[11]施工合同在1943年6月5日签订[12];第二个月,宾夕法尼亚大学摩尔电气工程学院以“PX项目”为代号秘密开始了对计算机的研究,约翰·格里斯特·布雷纳德担任首席研究员。赫尔曼·戈德斯汀说服军队资助这个项目,让他负责监督。[13]

ENIAC由美国宾夕法尼亚大学的约翰·莫克利和约翰·普雷斯珀·埃克特设计[14]。协助开发的设计工程师团队包括罗伯特·肖(函数表)、杰弗里·川楚(除法器/平方根器)、托马斯·凯特·夏普勒斯(主编程器)、弗兰克· (主编程器)、亚瑟·伯克(乘法器)、哈里·哈斯基(读取器/打印机)和杰克·戴维斯(累加器)。[15]1946年,研究人员从宾夕法尼亚大学辞职,成立了埃克特-莫克利计算机公司。

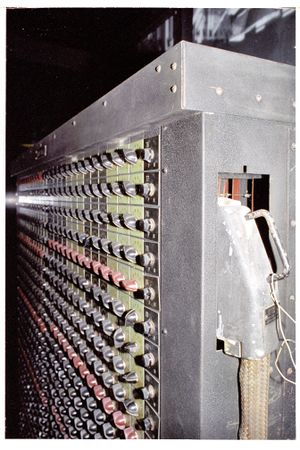

ENIAC是一台模块化计算机,由执行不同功能的独立面板组成。其中20个模块是累加器,不仅可以加减,还可以在内存中保存一个十位的十进制数。数字在这些单元之间通过几条通用总线(或托盘,如它们所称)传递。为了实现它的高速,面板必须发送和接收数字,计算,保存答案和触发下一个操作,所有这些都没有任何移动部件。其多功能性的关键是分支能力;它可以根据计算结果的信号触发不同的运算。

1.1 成分

组件构成到1956年运行结束时,ENIAC已装有20000根真空管;7200个晶体二极管;1500个继电器;70000个电阻;10000个电容;和大约500万个手工焊接接头。它重30多短吨(即27吨),尺寸大约为2.4米× 0.9米× 30米(8英尺× 3英尺× 98英尺),占地167平方米(1800平方英尺),耗电150千瓦。[16][17]这种电力需求导致了一个谣言,每当这台计算机开机时,费城的灯就会变暗。[18]输入可以从一台IBM的读卡器输入,输出则使用一台IBM的打卡机。这些卡可以使用IBM会计机(比如IBM 405)离线生成打印输出。

虽然ENIAC最初没有存储内存的系统,但这些穿孔卡可以用作外部内存存储。[19]1953年,巴勒斯公司制造的100字磁芯存储器被添加到ENIAC。[20]

ENIAC使用十位环形计数器存储数字;每个数字需要36个真空管,其中10个是构成环形计数器的触发器的双三极管。算术是通过用环形计数器的“计数”脉冲并在计数器“缠绕”时产生进位脉冲来实现的,其思想是电子模拟机械加法机的数字轮的操作。

ENIAC有20个十位数带符号累加器,使用十进制补码表示,每秒可以在其中任何一个累加器和一个源数据(如另一个累加器或常数发送器)之间执行5000次简单的加法或减法运算。还可以把几个累加器连接起来同时运行,因为并行运算,峰值运行速度可能要高得多。

可以将一个累加器的进位连接到另一个累加器,以执行双精度算术运算,但是累加器进位电路时序阻止了能获得更高精度的三个或更多的进位连接。ENIAC使用四个累加器(由一个特殊的乘法器单元控制)每秒可执行多达385次乘法运算;由一个特殊的除法器/平方根器单元控制的五个累加器,每秒可进行多达40次除运算或三次平方根运算。

ENIAC中的其他九个单元是启动单元(启动和停止机器)、循环单元(用于同步其他单元)、主编程器(控制“循环”序列)、读取器(控制一台IBM打孔卡读取器)、打印机(控制一台IBM打孔卡打孔器)、常量传送器和三个函数表。[21][22]

1.2 操作时间

罗哈斯和哈斯哈根(或威尔克斯)的参考文献[14]给出了更多关于运算时间的细节,这些时间与上述不同。

基本的机器周期是200微秒(循环单元中100千赫时钟的20个周期),或者进行十位数运算时每秒5000个周期。在一个周期内,ENIAC可以向寄存器中写入一个数字,从寄存器中读取一个数字,或者加减两个数字。

一个10位数乘以一个d位数(最多10位数)需要d+4个周期,所以一个10乘以10位数的乘法需要14个周期,即2800微秒——每秒357次。如果其中一个数字不足10位数,运算会更快。

除法和平方根用了13(d+1)个周期,其中d是运算结果数字(商或平方根)的位数。所以除法或平方根需要143个周期,即28600微秒——每秒35次的速率。(威尔克斯1956:20指出[14],产生10位数商的除法需要6毫秒。)如果结果位数少于十位,则速度更快。

1.3 可靠性

ENIAC使用当时普通的八脚电子管;十进制累加器由6SN7触发器制成,逻辑功能则使用6L7s、6SJ7s、6SA7s和6AC7s。[23] 大量6L6s和6V6s被用作线路驱动器,通过机架组件之间的电缆驱动脉冲传递。

几乎每天都有几根管子烧坏,导致ENIAC大约一半时间无法工作。特殊的高可靠性管子直到1948年才出现。然而,这些故障大多发生在预热和冷却期间,此时管式加热器和阴极处于最大热应力下。工程师将ENIAC的管子故障率降低到每两天一根管子的更可接受的水平。根据1989年对埃克特的一次采访,“我们大约每两天就有一个管子发生故障,我们可以在15分钟内找到问题所在。”[24]1954年,无故障持续运行最长的时间是116小时——接近5天。

2 编程编辑

ENIAC可以被编程来执行复杂的运算序列,包括循环、分支和子程序。然而,ENIAC并不是现有的存储程序的计算机,它只是一大堆算术机器,最初通过插板接线和三个便携式函数表(每个包含1200个十向开关)的组合将程序设置到机器中。[25][26]解决一个问题并将其映射到机器上的任务是很复杂的,通常需要几周的时间。由于将程序映射到机器上的复杂性,程序只有在对当前程序进行大量测试后才会改变。[27]在这个程序被写在纸上后,通过操纵它的开关和电缆把程序输入ENIAC的过程可能需要几天时间。接下来是一段时间的验证和调试,并辅以逐步执行程序的能力。一个使用ENIAC模拟器的模块化函数编程教程给人展示了ENIAC上的程序是什么样子的印象。[28][29]

ENIAC的六个主要程序员,凯·麦纽提、贝蒂·詹宁斯、贝蒂·斯奈德、玛琳·韦斯科夫、弗兰·比拉斯和鲁思·利彻曼,不仅决定了如何输入ENIAC程序,还了解了ENIAC的内部工作原理的理解。[30][31]程序员通常能够将bug缩小到一个单独的故障管子,定位后以便技术人员更换。[32]

2.1 程序员

凯·麦纽提、贝蒂·詹宁斯、贝蒂·斯奈德、玛琳·梅尔策、弗兰·比拉斯和露丝·利彻曼是ENIAC的第一批程序员。历史学家起初把它们误认为“冰箱女士”,即在机器前摆姿势的模特。[33]大多数妇女一生中在ENIAC上的工作没有得到认可。

这些早期的程序员是从宾夕法尼亚大学摩尔电气工程学院雇佣的大约200名女性计算员中挑选出来的。计算员的工作是计算科学研究或工程项目所需的数学公式的数值结果。他们通常用机械计算器来完成。这是当时为数不多的女性技术工作类别之一。[34]贝蒂·霍尔伯顿(内·斯奈德)继续帮助编写第一个生成式编程系统(SORT/MERGE),并与让·詹宁斯一起帮助设计第一台商用电子计算机UNIVAC和BINAC。[35]麦纽提开发了子程序的使用,以助于增强ENIAC的计算能力。

赫尔曼·戈德斯汀(Herman Goldstine)从开发ENIAC之前和期间一直用机械台式计算器和微分分析器计算弹道表的计算员中挑选程序员,他称之为操作员。在赫尔曼和阿黛尔·戈德斯汀(Adele Goldstine)的指导下,计算员研究了ENIAC的蓝图和物理结构,以确定如何操纵其开关和电缆,因为编程语言还不存在。尽管同时代的人认为编程是一项文书工作,并没有公开承认程序员对ENIAC的成功运转和问世的影响,但麦纽提、詹宁斯、斯奈德、韦斯科夫、比拉斯和利彻曼后来因其对计算的贡献而得到认可。

“程序员”和“操作员”的职称最初并不被认为是适合妇女的职业。第二次世界大战造成的劳动力短缺帮助妇女进入了该领域。[36] 然而,这一领域并不享有声望,引进女性被视为解放男性获得更高技能劳动力的一种方式。例如,美国国家航空咨询委员会在1942年说,“人们认为,通过将工程师从计算细节中解放出来,可以获得足够大的回报,抵消计算员工资上增加的费用。工程师们承认女性计算员比他们做这项工作更快更准确。这很大程度上是因为工程师们觉得他们的大学和工业经验会被纯粹重复的计算浪费和消磨”。[36]

在最初的六名程序员之后,一个由100名科学家组成的扩大团队被招募来继续在ENIAC上工作。其中有几位女性,包括洛莉亚·鲁思·戈登。[37] 阿黛尔·戈德斯汀(Adele Goldstine)撰写了ENIAC的原始技术说明。[38]

2.2 氢弹中的角色

虽然弹道研究实验室是ENIAC的赞助者,但是在这个为期三年的项目进行一年后,在洛斯阿拉莫斯国家实验室为氢弹项目工作的数学家约翰·冯·诺依曼注意到了这台计算机。[39]洛斯阿拉莫斯随后与ENIAC的关系如此密切,以至于第一次测试运行是计算氢弹相关数据,而不是火炮表。[39]这次测试的输入/输出数据是一百万张卡片。[39]

2.3 蒙特卡罗方法发展中的作用

与ENIAC在氢弹研制中的作用有关,它在蒙特卡罗方法中的作用越来越受到欢迎。参与最初核弹研发的科学家利用大量的人进行大量的计算(用当时的术语来说是“计算员”)来研究中子可能穿过各种材料的距离。约翰·冯·诺依曼和斯坦尼斯劳·乌拉姆意识到ENIAC的速度可以更快地完成这些计算。[39] 这个项目的成功展示了蒙特卡罗方法在科学上的价值。[40]

3 后来的发展编辑

1946年2月1日举行了一次新闻发布会,[41]并于1946年2月14日晚上向公众公布了竣工的机器[42],展示了它的能力。伊丽莎白·斯奈德和贝蒂·让·詹宁斯负责开发演示轨迹计划,尽管赫尔曼和阿黛尔·戈德斯汀对此功不可没[41]。第二天,这台机器在宾夕法尼亚大学正式投入使用[43]。没有一个参与机器编程或制作演示的女性被邀请参加正式的献词活动或随后举行的庆祝晚宴。[44]

原始合同金额为61700美元;最终成本几乎是500000美元(大约是今天的6400000美元)。它于1946年7月被美国陆军军械部正式接受。ENIAC于1946年11月9日因整修和内存升级而关闭,并于1947年转移到马里兰州阿伯丁试验场。在那里,1947年7月29日,它被打开并持续运行到1955年10月2日晚上11点45分。[45]

3.1 开发EDVAC的作用

在ENIAC于1946年夏天揭幕几个月后,作为“启动该领域研究的非凡努力”的一部分[45],五角大楼邀请“来自美国和英国的电子和数学领域的顶尖人物”[45]参加在宾夕法尼亚州费城举行的一系列48场讲座;统称为数字计算机设计的理论和技术——更常被称为摩尔学校讲座[45]。这些讲座中有一半是由ENIAC的发明者讲授的。[46]

ENIAC是独一无二的设计,从未被重复。1943年的设计冻结意味着计算机设计将缺少一些即将发展成熟的创新,尤其是缺乏存储程序的能力。埃克特和莫克利开始研究一种新的设计,后来被称为EDVAC,这种设计既简单又强大。特别是在1944年,埃克特撰写了他对一个存储单元(水银延迟线)的说明,这个存储单元可以同时保存数据和程序。为摩尔学校提供EDVAC咨询的约翰·冯·诺依曼参加了摩尔学校的会议,会上详细阐述了存储程序的概念。冯·诺伊曼写下了一套不完整的笔记(EDVAC报告初稿),旨在用作内部备忘录——用正式的逻辑语言描述、阐述和表达会议中形成的观点。ENIAC的管理员和安全员赫尔曼··戈德斯汀将初稿分发给许多政府和教育机构,激起了人们对构建新一代电子计算机的广泛兴趣,包括英国剑桥大学的电子延迟存储自动计算器(EDSAC)和美国标准局的SEAC。[47]

3.2 改进

1947年后对ENIAC进行了许多改进,包括使用函数表作为程序只读存储器(ROM)的原始只读存储编程机制[47][48][49],之后通过设置开关进行编程。[50]理查德·克利平格尔和他的团队,以及戈尔茨廷夫妇,已经完成了这个想法的几个变种实现[51],并被纳入ENIAC专利[52]。克利平格就要实施的指令集咨询了冯·诺依曼[47][53][54]。克利平格尔想到了三地址架构,而冯·诺依曼提出了一个单地址架构,因为它更容易实现。一个累加器(#6)的三位数字用作程序计数器,另一个累加器(#15)用作主累加器,第三个累加器(#8)被用作从函数表中读取数据的地址指针,另外的大部分累加器(1–5、7、9–14、17–19)用于数据存储。

1948年3月,转换器单元被安装上[55],这使得通过读卡器使用标准的IBM卡片进行编程成为可能[56][57]。蒙特卡洛问题新编码技术的“第一次生产运行”在4月份随之而来[55][58]。ENIAC搬到阿伯丁后,还建造了一个记忆寄存器面板,但不起作用。还增加了一个用于打开和关闭机器的小型主控制单元。[59]

ENIAC存储程序的编程由贝蒂·詹宁斯(Betty Jennings)、克利平格尔(Clippinger)、阿黛尔·戈德斯汀(Adele Goldstine)等人完成。[60][47][48]1948年4月[61],它首次被展示为存储程序计算机,运行了一个由阿黛尔·戈德斯汀为约翰·冯·诺依曼写的程序。这种修改将ENIAC的速度降低了6倍,并且限制了并行计算能力,但是由于它将重新编程的时间[47][54]从几天减少到了几小时,因此人们认为性能上的损失也是值得的。分析还显示,由于电子计算速度和机电输入/输出速度之间的差异,即使不利用原始机器的并行能力,几乎现实世界中的每个问题也完全是受输入/输出约束的。大多数计算仍然是受输入/输出约束的,哪怕这种修改让速度降低之后。

1952年初,增加了高速移位器,将移位速度提高了五倍。1953年7月,系统增加了一个100字的扩展核心存储器,使用BCD码(二进制编码十进制数)和Excess-3(加三码)数字表示。为了支持这种扩展存储器,ENIAC配备了新的函数表选择器、存储器地址选择器、脉冲整形电路,并且在编程机制中增加了三个新的指令。[47]

4 与其他早期计算机的比较编辑

自阿基米德时代起,机械计算机就存在了,但20世纪30年代和40年代被认为是现代计算机时代的开始。

ENIAC就像IBM哈佛马克一号和德国Z3一样,可以运行任意数学运算系列,但是不是从磁带上读取数据。像英国Colossus一样,它由插板和开关来编程。ENIAC将全面,图灵完全的可编程能力与电子计算的高速性结合在一起。阿坦纳索夫-贝里计算机(ABC)、ENIAC和Colossus都使用热离子阀(真空管)。ENIAC的寄存器执行十进制运算,而不是像Z3、ABC和Colossus那样的二进制运算。

1948年4月以前, ENIAC像Colossus一样,需要重新布线来重新编程。[62]1948年6月,曼彻斯特婴儿(Manchester Baby)运行了它的第一个程序,并赢得了第一台电子存储程序计算机的荣誉。[63][64][65]虽然在ENIAC的开发过程中构想了一种存储程序计算机配以程序和数据的组合存储器的想法,但最初并没有在ENIAC中实现,因为二战的优先权需要这台机器尽快完工,并且ENIAC的20个存储位置也太小了,不足以存储数据和程序。

4.1 公众认知

Z3和Colossus是在第二次世界大战期间彼此独立发展起来的,也是独立于ABC 和 ENIAC开发的。1942年,在约翰·阿坦纳索夫被叫到华盛顿特区为美国海军做物理研究后,爱荷华州立大学在ABC上的工作就停止了,随后ABC被拆除。[66]Z3在1943年盟军对柏林的轰炸中被摧毁。由于十台Colossus机器是英国战争工作的一部分,它们的存在直到20世纪70年代末才被解密,尽管只有英国相关人员和受邀的美国人才能获悉它们的性能。相比之下,ENIAC在1946年接受了媒体的采访,“吸引了全世界的想象力”。因此,先前的计算历史在新闻报道和分析上没有像这一时期一样全面综合。除了两台以外,所有的Colossus机器都在1945年被拆除了;剩下的两台在20世纪60年代以前一直被英国政府通信总部(GCHQ)用来解密苏联的信息。[67][68]ENIAC的公开演示是由斯奈德和詹宁斯开发的,他们制作了一个演示程序,可以在15秒内计算出导弹的弹道,这项任务对于一名人类计算员来说需要花费数周的时间。[69]

4.2 专利

出于各种原因(包括1941年6月莫克利对阿坦纳索夫-贝里计算机(ABC)的考察,原型机在1939年由约翰·阿坦纳索夫和克利福德·贝里完成),于1947年提交申请并于1964年获得授权的ENIAC的美国专利3,120,606,依据联邦法院对霍尼韦尔起诉斯佩里·兰德(Honeywell诉Sperry Rand)的案件在1973年里程碑式的裁决而被认定无效,促使了将电子数字计算机的发明公之于众,并为阿坦纳索夫作为第一台电子数字计算机的发明者提供了合法承认。

5 ENIAC主要部件编辑

主要部件有40块面板和三个便携式函数表(分别命名为A、B和C)。面板的布局是(顺时针,从左墙面开始):

- 左墙面

- 启动单元

- 循环单元

- 主编程器-面板1和2

- 函数表1 -面板1和2

- 累加器1

- 累加器2

- 除法器和平方根器

- 累加器3

- 累加器4

- 累加器5

- 累加器6

- 累加器7

- 累加器8

- 累加器9

- 后墙面

- 累加器10

- 高速乘法器-面板1、2和3

- 累加器11

- 累加器12

- 累加器13

- 累加器14

- 右墙面

- 累加器15

- 累加器16

- 累加器17

- 累加器18

- 函数表2 -面板1和2

- 函数表3 -面板1和2

- 累加器19

- 累加器20

- 常数传送器-面板1、2和3

- 打印机-面板1、2和3

一个IBM的读卡器连接到常数传送器面板3,一个IBM的打卡机连接到打印机面板2。便携式函数表可以连接到函数表1、2和3。[69]

5.1 展出的部件

ENIAC的部件由以下机构持有:

- 宾夕法尼亚大学工程和应用科学学院拥有最初四十个面板中的四个(累加器#18、常量发送器面板2、主编程器面板2和循环单元)和ENIAC三个函数表(功能表B)中的一个(从史密森尼学会借出)。[69]

- 史密森尼学会拥有五个面板(累加器2、19和20;常量发送器面板1和3;除法器和平方根器;函数表2面板1;函数表3面板2;高速乘法器面板1和2;打印机面板1;启动单元)[69]在华盛顿特区的美国国家历史博物馆里[70] (但显然目前没有展出)。

- 伦敦科学博物馆拥有一个接收器单元,在展览中。

- 加利福尼亚州山景城的计算机历史博物馆有三块面板(累加器#12、函数表2面板2以及打印机面板3)和便携式函数表C(从史密森尼学会借出)。[69]

- 安阿伯的密歇根大学有四块面板(两个累加器、高速乘法器面板3和主编程器面板2),[69]由亚瑟·伯克保管。

- 位于马里兰州阿伯丁试验场的美国陆军军械博物馆,也就是使用过ENIAC的地方,现拥有一个便携式函数表A。

- 截至2014年10月,希尔堡的美国陆军野战炮兵博物馆获得了七块ENIAC面板,这些面板以前由德克萨斯州普莱诺的佩罗集团(The Perot Group)收藏。[70]有累加器#7、#8、#11和# 17;[71]连接到函数表#1的面板#1和#2,[69]面板的背面则展示了它的真空管。一个真空管模块也在展出。

- 位于纽约西点的美国军事学院有一个来自ENIAC的数据录入终端。

- 德国帕德伯恩的亨氏.尼克斯多夫博物馆论坛拥有三块面板(打印机面板2和高速函数表)[69](从史密森尼学会借出)。2014年,博物馆决定重建其中一块加法器面板——重建的部分拥有如同原机复制品一般的外观和感关。[72]

6 承认编辑

认可ENIAC在1987年被命名为IEEE里程碑。[73]

1996年,为了纪念ENIAC诞生50周年,宾夕法尼亚大学赞助了一个名为“芯片上ENIAC”的项目,在这个项目中,一个7.44毫米乘5.29毫米的非常小的硅计算机芯片被构建成具有与ENIAC相同的功能。尽管这款20 MHz芯片比ENIAC快很多倍,但它的速度依然比20世纪90年代末的当代微处理器慢很多。[74][75][76]

1997年,六名完成ENIAC大部分编码工作的女性入选国际技术女性名人堂[77][77]。莱安·埃里克森在2010年的纪录片《绝密罗西斯:二战中的女性“电脑”》中正视了ENIAC程序员的角色。[78]凯特·麦克马洪2014年的一部纪录片短片《计算员们》,讲述了这六位程序员的故事;这是凯瑟琳·克雷曼和她的团队20年研究的结果,也是ENIAC程序员项目中的一部分。[78][78]

2011年,为纪念ENIAC问世65周年,费城宣布2月15日为ENIAC日。[79]

2016年2月15日,ENIAC庆祝其诞生70周年。[80]

7 笔记编辑

- Haigh. et. al. list accumulators 7, 8, 13, and 17, but 2018 photos show 7, 8, 11, and 17.

- Eckert Jr., John Presper and Mauchly, John W.; Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, United States Patent Office, US Patent 3,120,606, filed 1947-06-26, issued 1964-02-04; invalidated 1973-10-19 after court ruling on Honeywell v. Sperry Rand.

- Weik, Martin H. "The ENIAC Story". Ordnance. 708 Mills Building - Washington, DC: American Ordnance Association (January–February 1961). Archived from the original on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- ,第97页

- Shurkin, Joel (1996). Engines of the mind: the evolution of the computer from mainframes to microprocessors. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31471-7.

- Moye, William T. (January 1996). "ENIAC: The Army-Sponsored Revolution". US Army Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2017-05-21. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- p.103 (1999): "ENIAC correctly showed that Teller's scheme would not work, but the results led Teller and Ulam to come up with another design together."

- Richard Rhodes (1995). "chapter 13". Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. p. 251. The first problem assigned to the first working electronic digital computer in the world was the hydrogen bomb. […] The ENIAC ran a first rough version of the thermonuclear calculations for six weeks in December 1945 and January 1946.

- *"ENIAC on Trial – 1. Public Use". www.ushistory.org. Search for 1945. Retrieved 2018-05-16. The ENIAC machine […] was reduced to practice no later than the date of commencement of the use of the machine for the Los Alamos calculations, December 10, 1945.

- About the court case (more sources): Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp..

- Brain used in the press as a metaphor became common during the war years. Looking, for example, at Life magazine: 1937-08-16, p.45 Overseas Air Lines Rely on Magic Brain (RCA Radiocompass). 1942-03-09 p.55 the Magic Brain—is a development of RCA engineers (RCA Victrola). 1942-12-14 p.8 Blanket with a Brain does the rest! (GE Automatic Blanket). 1943-11-08 p.8 Mechanical brain sights gun (How to boss a BOFORS!)

- "ENIAC". ENIAC USA 1946. History of Computing Project. 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- Dalakov, Georgi. "ENIAC". History of Computers. Georgi Dalakov. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2017-04-15.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- Wilkes, M. V. (1956). Automatic Digital Computers. New York: John Wiley & Sons. QA76.W5 1956.

- UShistory.org ENIAC Invetors Retrieved 2016-02-04 USHistory.org ENIAC Inventors.

- "ENIAC". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- Weik, Martin H. (December 1955). Ballistic Research Laboratories Report No. 971: A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems. Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD: United States Department of Commerce Office of Technical Services. p. 41. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- Farrington, Gregory (March 1996). ENIAC: Birth of the Information Age. Popular Science. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- "ENIAC in Action: What it Was and How it Worked". ENIAC: Celebrating Penn Engineering History. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- Martin, Jason (1998-12-17). "Past and Future Developments in Memory Design". Past and Future Developments in Memory Design. University of Maryland. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- The original photo can be seen in the article: Rose, Allen (April 1946). "Lightning Strikes Mathematics". Popular Science: 83–86. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- , Section I: General Description of the ENIAC – The Function Tables.

- Goldstine, Adele (1946). Source (20.4 MB). "A Report on the ENIAC". Ftp.arl.mil. 1 (1). Chapter 1 -- Introduction: 1.1.2. The Units of the ENIAC.

- ,第756–767页

- Randall 5th, Alexander (2006-02-14). "A lost interview with ENIAC co-inventor J. Presper Eckert". Computer World. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- Grier, David (July–September 2004). "From the Editor's Desk". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 26 (3): 2–3. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2004.9. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- Cruz, Frank (2013-11-09). "Programming the ENIAC". Programming the ENIAC. Columbia University. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- Alt, Franz (July 1972). "Archaelogy of computers: reminiscences, 1945-1947". Communications of the ACM. 15 (7): 693–694. doi:10.1145/361454.361528. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- Schapranow, Matthieu-P. (1 June 2006). "ENIAC tutorial - the modulo function". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- Description of Lehmer's program computing the exponent of modulo 2 prime

- De Mol, Liesbeth; Bullynck, Maarten (2008). "A Week-End Off: The First Extensive Number-Theoretical Computation on ENIAC". In Beckmann, Arnold; Dimitracopoulos, Costas; Löwe, Benedikt. Logic and Theory of Algorithms: 4th Conference on Computability in Europe, CiE 2008 Athens, Greece, June 15-20, 2008, Proceedings (in 英语). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 158–167. ISBN 9783540694052.

- "ENIAC Programmers Project". eniacprogrammers.org. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- Donaldson James, Susan (2007-12-04). "First Computer Programmers Inspire Documentary". ABC News. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- Fritz, W. Barkley (1996). "The Women of ENIAC" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 18 (3): 13–28. doi:10.1109/85.511940. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- "Meet the 'Refrigerator Ladies' Who Programmed the ENIAC". Mental Floss. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- Light, Jennifer S. (1999). "When Computers Were Women" (PDF). Technology and Culture. 40 (3): 455–483. doi:10.1353/tech.1999.0128 (inactive 2019-03-14). Retrieved 2015-03-09.

- Grier, David (2007). When Computers Were Human. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400849369. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- Beyer, Kurt (2012). Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age. London, Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780262517263.

- Isaacson, Walter (18 September 2014). "Walter Isaacson on the Women of ENIAC". Fortune (in 英语). Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- "Invisible Computers: The Untold Story of the ENIAC Programmers". Witi.com. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- Gumbrecht, Jamie (February 2011). "Rediscovering WWII's female 'computers'". CNN. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- "Festival 2014: The Computers". SIFF. Archived from the original on 2015-03-12. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- Light, Jennifer (July 1999). "When Computers were Women" (PDF). Technology and Culture. 40, 3: 455–483.

- Sullivan, Patricia (2009-07-26). "Gloria Gordon Bolotsky, 87; Programmer Worked on Historic ENIAC Computer". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-08-19.

- https://www.arl.army.mil/www/default.cfm?page=148

- Mazhdrakov, Metodi; Benov, Dobriyan; Valkanov, Nikolai (2018). The Monte Carlo Method. Engineering Applications. ACMO Academic Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-619-90684-3-4.

- Kean, Sam (2010). The Disappearing Spoon. New York: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-0-316-05163-7.

- Light, Jennifer S. (July 1999). "When Computers Were Women". Technology and Culture. 40: 455–483.

- Kennedy, Jr., T. R. (1946-02-15). "Electronic Computer Flashes Answers". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-07-10. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp., 180 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 673, p. 20, finding 1.1.3 (U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota, Fourth Division 1973). “The ENIAC machine which embodied 'the invention' claimed by the ENIAC patent was in public use and non-experimental use for the following purposes, and at times prior to the critical date: ... Formal dedication use February 15, 1946 ...”

- Evans, Claire L. (2018-03-06). Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet (in 英语). Penguin. p. 51. ISBN 9780735211766.

- p.140 (1999)

- p.140 (1999): Eckert gave eleven lectures, Mauchly gave six, Goldstine gave six. von Neumann, who was to give one lecture, didn't show up; the other 24 were spread among various invited academics and military officials.

- "Eniac". Epic Technology for Great Justice (in 英语). Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- Goldstine, Adele K. (10 July 1947). Central Control for ENIAC. p. 1. Unlike the later 60- and 100-order codes this one [51 order code] required no additions to ENIAC’s original hardware. It would have worked more slowly and offered a more restricted range of instructions but the basic structure of accumulators and instructions changed only slightly.

- *,233-234, 270; search string: eniac Adele 1947

By July 1947 von Neumann was writing: "I am much obliged to Adele for her letters. Nick and I are working with her new code, and it seems excellent."

- ,Section IV: Summary of Orders

- ,第44–48页

- Pugh, Emerson W. (1995). "Notes to Pages 132-135". Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology (in 英语). MIT Press. p. 353. ISBN 9780262161473.

- , pp. 44-45.

- , p. 44.

- , INTRODUCTION.

- , 233-234, 270; search string: eniac Adele 1947.

- , pp. 47-48.

- , Section VIII: Modified ENIAC.

- Fritz, W. Barkley (1949). "Description and Use of the ENIAC Converter Code". Technical Note (141). Section 1. – Introduction, p. 1. At present it is controlled by a code which incorporates a unit called the Converter as a basic part of its operation, hence the name ENIAC Converter Code. These code digits are brought into the machine either through the Reader from standard IBM cards* or from the Function Tables (...). (...) * The card control method of operation is used primarily for testing and the running of short highly iterative problems and is not discussed in this report.

- Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (July–September 2014). "Los Alamos Bets On ENIAC: Nuclear Monte Carlo Simulations 1947-48". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing (in 英语). 36 (3): 42–63. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2014.40. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- Thomas Haigh; Mark Priestley; Crispen Rope (2016). ENIAC in Action:Making and Remaking the Modern Computer. MIT Press. pp. 113–14. ISBN 978-0-262-03398-5.

- ,INTRODUCTION

- Full names: ,第44页

- Thomas Haigh; Mark Priestley; Crispen Rope (2016). ENIAC in Action:Making and Remaking the Modern Computer. MIT Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-262-03398-5.

- See

- "Programming the ENIAC: an example of why computer history is hard | @CHM Blog | Computer History Museum". www.computerhistory.org (in 英语).

- , pp. 48-54.

- Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (January–March 2014). "Reconsidering the Stored Program Concept". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 36 (1): 9–10.

- , p. 106.

- , p. 2.

- Ward, Mark (5 May 2014), How GCHQ built on a colossal secret, BBC News

- Haigh, Thomas; Preistley, Mark; Rope, Xrispen (2016). ENIAC in Action. MIT Press. pp. 46, 264. ISBN 978-0-262-03398-5.

- Meador, Mitch (2014-10-29). "ENIAC: First Generation Of Computation Should Be A Big Attraction At Sill". The Lawton Constitution. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- "Meet the iPhone's 30-ton ancestor: Inside the project to rebuild one of the first computers". TechRepublic (in 英语). Bringing the Eniac back to life.

- "Milestones:Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, 1946". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- "Looking Back At ENIAC: Commemorating A Half-Century Of Computers In The Reviewing System". The Scientist Magazine® (in 英语).

- Van Der Spiegel, Jan (1996). "PENN PRINTOUT - The University of Pennsylvania's Online Computing Magazine". Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- Van Der Spiegel, Jan (1995-05-09). "ENIAC-on-a-Chip". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- Brown, Janelle (1997-05-08). "Wired: Women Proto-Programmers Get Their Just Reward". Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- "ENIAC Programmers Project". ENIAC Programmers Project. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- "Resolution No. 110062: Declaring February 15 as "Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer (ENIAC) Day" in Philadelphia and honoring the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Sciences" (PDF). 2011-02-10. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Kim, Meeri (2016-02-11). "70 years ago, six Philly women became the world's first digital computer programmers". Retrieved 2016-10-17 – via www.phillyvoice.com.

参考文献

- [1]

^Eckert Jr., John Presper and Mauchly, John W.; Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, United States Patent Office, US Patent 3,120,606, filed 1947-06-26, issued 1964-02-04; invalidated 1973-10-19 after court ruling on Honeywell v. Sperry Rand..

- [2]

^Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

- [3]

^Goldstine & Goldstine 1946,第97页.

- [4]

^Shurkin, Joel (1996). Engines of the mind: the evolution of the computer from mainframes to microprocessors. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31471-7..

- [5]

^Moye, William T. (January 1996). "ENIAC: The Army-Sponsored Revolution". US Army Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2017-05-21. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [6]

^Scott McCartney p.103 (1999): "ENIAC correctly showed that Teller's scheme would not work, but the results led Teller and Ulam to come up with another design together.".

- [7]

^Richard Rhodes (1995). "chapter 13". Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. p. 251. The first problem assigned to the first working electronic digital computer in the world was the hydrogen bomb. […] The ENIAC ran a first rough version of the thermonuclear calculations for six weeks in December 1945 and January 1946..

- [8]

^*"ENIAC on Trial – 1. Public Use". www.ushistory.org. Search for 1945. Retrieved 2018-05-16. The ENIAC machine […] was reduced to practice no later than the date of commencement of the use of the machine for the Los Alamos calculations, December 10, 1945. About the court case (more sources): Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp...

- [9]

^Brain used in the press as a metaphor became common during the war years. Looking, for example, at Life magazine: 1937-08-16, p.45 Overseas Air Lines Rely on Magic Brain (RCA Radiocompass). 1942-03-09 p.55 the Magic Brain—is a development of RCA engineers (RCA Victrola). 1942-12-14 p.8 Blanket with a Brain does the rest! (GE Automatic Blanket). 1943-11-08 p.8 Mechanical brain sights gun (How to boss a BOFORS!).

- [10]

^"ENIAC". ENIAC USA 1946. History of Computing Project. 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2016-05-18..

- [11]

^Dalakov, Georgi. "ENIAC". History of Computers. Georgi Dalakov. Retrieved 2016-05-23..

- [12]

^Goldstine & Goldstine 1946.

- [13]

^"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2017-04-15.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link).

- [14]

^Wilkes, M. V. (1956). Automatic Digital Computers. New York: John Wiley & Sons. QA76.W5 1956..

- [15]

^UShistory.org ENIAC Invetors Retrieved 2016-02-04 USHistory.org ENIAC Inventors..

- [16]

^"ENIAC". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [17]

^Weik, Martin H. (December 1955). Ballistic Research Laboratories Report No. 971: A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems. Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD: United States Department of Commerce Office of Technical Services. p. 41. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [18]

^Farrington, Gregory (March 1996). ENIAC: Birth of the Information Age. Popular Science. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [19]

^"ENIAC in Action: What it Was and How it Worked". ENIAC: Celebrating Penn Engineering History. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2016-05-17..

- [20]

^Martin, Jason (1998-12-17). "Past and Future Developments in Memory Design". Past and Future Developments in Memory Design. University of Maryland. Retrieved 2016-05-17..

- [21]

^Clippinger 1948, Section I: General Description of the ENIAC – The Function Tables..

- [22]

^Goldstine, Adele (1946). Source (20.4 MB). "A Report on the ENIAC". Ftp.arl.mil. 1 (1). Chapter 1 -- Introduction: 1.1.2. The Units of the ENIAC..

- [23]

^Burks 1947,第756–767页.

- [24]

^Randall 5th, Alexander (2006-02-14). "A lost interview with ENIAC co-inventor J. Presper Eckert". Computer World. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [25]

^Grier, David (July–September 2004). "From the Editor's Desk". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 26 (3): 2–3. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2004.9. Retrieved 2016-05-16..

- [26]

^Cruz, Frank (2013-11-09). "Programming the ENIAC". Programming the ENIAC. Columbia University. Retrieved 2016-05-16..

- [27]

^Alt, Franz (July 1972). "Archaelogy of computers: reminiscences, 1945-1947". Communications of the ACM. 15 (7): 693–694. doi:10.1145/361454.361528. Retrieved 2016-05-16..

- [28]

^Schapranow, Matthieu-P. (1 June 2006). "ENIAC tutorial - the modulo function". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 2017-03-04..

- [29]

^Description of Lehmer's program computing the exponent of modulo 2 prime De Mol, Liesbeth; Bullynck, Maarten (2008). "A Week-End Off: The First Extensive Number-Theoretical Computation on ENIAC". In Beckmann, Arnold; Dimitracopoulos, Costas; Löwe, Benedikt. Logic and Theory of Algorithms: 4th Conference on Computability in Europe, CiE 2008 Athens, Greece, June 15-20, 2008, Proceedings (in 英语). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 158–167. ISBN 9783540694052..

- [30]

^"ENIAC Programmers Project". eniacprogrammers.org. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [31]

^Donaldson James, Susan (2007-12-04). "First Computer Programmers Inspire Documentary". ABC News. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [32]

^Fritz, W. Barkley (1996). "The Women of ENIAC" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 18 (3): 13–28. doi:10.1109/85.511940. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-12..

- [33]

^"Meet the 'Refrigerator Ladies' Who Programmed the ENIAC". Mental Floss. Retrieved 2016-06-16..

- [34]

^Grier, David (2007). When Computers Were Human. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400849369. Retrieved 2016-11-24..

- [35]

^Beyer, Kurt (2012). Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age. London, Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780262517263..

- [36]

^Light, Jennifer (July 1999). "When Computers were Women" (PDF). Technology and Culture. 40, 3: 455–483..

- [37]

^Sullivan, Patricia (2009-07-26). "Gloria Gordon Bolotsky, 87; Programmer Worked on Historic ENIAC Computer". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-08-19..

- [38]

^https://web.archive.org/web/20221025173621/https://www.arl.army.mil/www/default.cfm?page=148.

- [39]

^Goldstine 1972.

- [40]

^Kean, Sam (2010). The Disappearing Spoon. New York: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-0-316-05163-7..

- [41]

^Light, Jennifer S. (July 1999). "When Computers Were Women". Technology and Culture. 40: 455–483..

- [42]

^Kennedy, Jr., T. R. (1946-02-15). "Electronic Computer Flashes Answers". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-07-10. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [43]

^Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp., 180 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 673, p. 20, finding 1.1.3 (U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota, Fourth Division 1973). “The ENIAC machine which embodied 'the invention' claimed by the ENIAC patent was in public use and non-experimental use for the following purposes, and at times prior to the critical date: ... Formal dedication use February 15, 1946 ...”.

- [44]

^Evans, Claire L. (2018-03-06). Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet (in 英语). Penguin. p. 51. ISBN 9780735211766..

- [45]

^Weik, Martin H. "The ENIAC Story". Ordnance. 708 Mills Building - Washington, DC: American Ordnance Association (January–February 1961). Archived from the original on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2015-03-29..

- [46]

^Scott McCartney p.140 (1999): Eckert gave eleven lectures, Mauchly gave six, Goldstine gave six. von Neumann, who was to give one lecture, didn't show up; the other 24 were spread among various invited academics and military officials..

- [47]

^"Eniac". Epic Technology for Great Justice (in 英语). Retrieved 2017-01-28..

- [48]

^Goldstine, Adele K. (10 July 1947). Central Control for ENIAC. p. 1. Unlike the later 60- and 100-order codes this one [51 order code] required no additions to ENIAC’s original hardware. It would have worked more slowly and offered a more restricted range of instructions but the basic structure of accumulators and instructions changed only slightly..

- [49]

^*Goldstine 1972,233-234, 270; search string: eniac Adele 1947 By July 1947 von Neumann was writing: "I am much obliged to Adele for her letters. Nick and I are working with her new code, and it seems excellent." Clippinger 1948,Section IV: Summary of Orders Haigh,Priestley & Rope(2014),第44–48页.

- [50]

^Pugh, Emerson W. (1995). "Notes to Pages 132-135". Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology (in 英语). MIT Press. p. 353. ISBN 9780262161473..

- [51]

^Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014, pp. 44-45..

- [52]

^Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014, p. 44..

- [53]

^Clippinger 1948, INTRODUCTION..

- [54]

^Goldstine 1972, 233-234, 270; search string: eniac Adele 1947..

- [55]

^Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014, pp. 47-48..

- [56]

^Clippinger 1948, Section VIII: Modified ENIAC..

- [57]

^Fritz, W. Barkley (1949). "Description and Use of the ENIAC Converter Code". Technical Note (141). Section 1. – Introduction, p. 1. At present it is controlled by a code which incorporates a unit called the Converter as a basic part of its operation, hence the name ENIAC Converter Code. These code digits are brought into the machine either through the Reader from standard IBM cards* or from the Function Tables (...). (...) * The card control method of operation is used primarily for testing and the running of short highly iterative problems and is not discussed in this report..

- [58]

^Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (July–September 2014). "Los Alamos Bets On ENIAC: Nuclear Monte Carlo Simulations 1947-48". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing (in 英语). 36 (3): 42–63. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2014.40. Retrieved 2018-11-13..

- [59]

^Thomas Haigh; Mark Priestley; Crispen Rope (2016). ENIAC in Action:Making and Remaking the Modern Computer. MIT Press. pp. 113–14. ISBN 978-0-262-03398-5..

- [60]

^Clippinger 1948,INTRODUCTION Full names: Haigh,Priestley & Rope(2014),第44页.

- [61]

^Thomas Haigh; Mark Priestley; Crispen Rope (2016). ENIAC in Action:Making and Remaking the Modern Computer. MIT Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-262-03398-5..

- [62]

^See #Improvements.

- [63]

^"Programming the ENIAC: an example of why computer history is hard | @CHM Blog | Computer History Museum". www.computerhistory.org (in 英语)..

- [64]

^Haigh, Priestley & Rope 2014, pp. 48-54..

- [65]

^Haigh, Thomas; Priestley, Mark; Rope, Crispin (January–March 2014). "Reconsidering the Stored Program Concept". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 36 (1): 9–10..

- [66]

^Copeland 2006, p. 106..

- [67]

^Copeland 2006, p. 2..

- [68]

^Ward, Mark (5 May 2014), How GCHQ built on a colossal secret, BBC News.

- [69]

^Isaacson, Walter (18 September 2014). "Walter Isaacson on the Women of ENIAC". Fortune (in 英语). Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-14..

- [70]

^Light, Jennifer S. (1999). "When Computers Were Women" (PDF). Technology and Culture. 40 (3): 455–483. doi:10.1353/tech.1999.0128 (inactive 2019-03-14). Retrieved 2015-03-09..

- [71]

^Haigh. et. al. list accumulators 7, 8, 13, and 17, but 2018 photos show 7, 8, 11, and 17..

- [72]

^"Meet the iPhone's 30-ton ancestor: Inside the project to rebuild one of the first computers". TechRepublic (in 英语). Bringing the Eniac back to life..

- [73]

^"Milestones:Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, 1946". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 2011-08-03..

- [74]

^"Looking Back At ENIAC: Commemorating A Half-Century Of Computers In The Reviewing System". The Scientist Magazine® (in 英语)..

- [75]

^Van Der Spiegel, Jan (1996). "PENN PRINTOUT - The University of Pennsylvania's Online Computing Magazine". Retrieved 2016-10-17..

- [76]

^Van Der Spiegel, Jan (1995-05-09). "ENIAC-on-a-Chip". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2009-09-04..

- [77]

^"Invisible Computers: The Untold Story of the ENIAC Programmers". Witi.com. Retrieved 2015-03-10..

- [78]

^Gumbrecht, Jamie (February 2011). "Rediscovering WWII's female 'computers'". CNN. Retrieved 2011-02-15..

- [79]

^"Resolution No. 110062: Declaring February 15 as "Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer (ENIAC) Day" in Philadelphia and honoring the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Sciences" (PDF). 2011-02-10. Retrieved 2014-08-13..

- [80]

^Kim, Meeri (2016-02-11). "70 years ago, six Philly women became the world's first digital computer programmers". Retrieved 2016-10-17 – via www.phillyvoice.com..

暂无