太阳系外行星

编辑太阳系外行星,[1]又称系外行星,是位于太阳系之外的行星。太阳系外行星的第一个证据是在1917年发现的,但是并没有被验证。 第一次对太阳系外行星的科学探测是在1988年,这颗行星在2013年被确认为系外行星。第一次确定的探测发生在1992年。截止至2019年12月,总共有在2971个星系中的3976个行星被确认,其中653个星系有多于一个的行星。

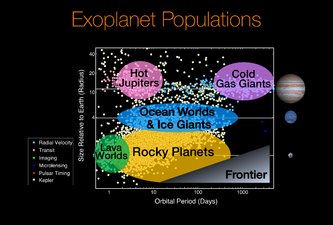

探测系外行星的方法有许多。目前,通过过境测光法和多普勒光谱学法发现的行星最多,但这些方法有明显的观测偏差,更偏向于探测恒星附近的行星。因此,85%探测到的外行星位于潮汐锁定区内。[2]在一些情况下,一颗恒星附近可以观察到多个行星。大约每五个类太阳恒星 中,有一个是“地球大小的”可居住区的行星。[3]假设银河系中有两千亿颗恒星,那么就有一百一十亿颗潜在的可居住的地球大小的行星,如果计算中包括围绕众多红矮星运行的行星,这个数字将达到四百亿。[4]

已知质量最小的行星是德拉格尔(也称为PSR B1257+12 A或PSR B1257+12 b),它的质量大约是月球质量的两倍。美国宇航局太阳系外行星档案中最大的行星在公元前2562年被记载,[5][6]它的质量大约是木星质量的30倍,尽管根据某些行星的定义(基于氘的核聚变[7]),它太大所以不可能是一颗行星,而是一颗褐矮星。有些行星离它们的恒星非常近,以至于它们只需要几个小时就能绕轨道运行,还有一些行星离它们非常远,以至于它们需要几千年才能绕轨道运行。有些距离恒星太远的行星,很难判断它们是否还受引力束缚。迄今为止,几乎所有被探测到的行星都在银河系内。尽管如此,有证据表明,银河系外的行星,即银河系以外更远的星系中的系外行星,可能存在。[8][9]最近的外行星是比邻星b,距地球4.2光年(1.3秒差距),它围绕着离太阳最近的恒星比邻星运行。[10]

太阳系外行星的发现增强了人们对寻找外星生命的兴趣。人们对运行在恒星的可居住区周围的行星特别感兴趣,因为这些区域可能存在液态水,而液态水是地球表面生命存在的先决条件。行星的可居住性研究还参考了其他一系列因素,来决定行星是否适合容纳生命。[11]

除了系外行星,宇宙中还存在不围绕任何恒星运行的流浪行星。这些行星往往被认为是一个独立的类别,尤其如果它们是气态巨行星,在这种情况下,它们通常被视为亚棕矮星,如WISE 0855-0714。[12]银河系中的流浪行星可能有数十亿颗,甚至更多。[13][14]

目录编辑

1 命名系统编辑

《指定系外行星公约》是国际天文学联盟(IAU)采用的命名多星系统的延伸。对于围绕一颗恒星运行的系外行星来说,这个名称通常是通过取其母星的名字,或者更常见的是,加上一个小写字母来形成的。[15]星系中发现的第一颗行星被命名为“b”(母星被认为是“a”),之后的行星被命名为后续字母。如果同一系统中的几颗行星同时被发现,离恒星最近的一颗会得到下一个字母,然后是按轨道大小顺序来排列的其他行星。临时的IAU认可的标准存在,以适应环双星的命名。少数系外行星有IAU认可的专有名称。除此之外还有其他命名系统。

2 探测历史编辑

几个世纪以来,科学家、哲学家和科幻作家都怀疑太阳系外行星的存在,[16]但是没有办法探测到它们,或者知道它们的频率,也无法了解到它们与太阳系的行星有多相似。天文学家否决了十九世纪提出的各种探测主张。早在1917年就发现了太阳系外行星(范·马嫩2号)的第一个证据,但是并没有被验证。[17]在1988年,太阳系外行星疑似首次被科学家探测到。不久之后,首个探测在1992年被确认,同时发现了几颗围绕脉冲星PSR B1257+12运行的地球质量的行星。[17]围绕主序列恒星运行的系外行星的首次确认是在1995年,当时发现了一颗巨大的行星,围绕在51 Pegasi星的四天轨道附近。一些系外行星已经通过望远镜直接成像,但是绝大多数行星是被间接地探测到的,例如利用过境测光法和径向速度法。在2018年2月,研究人员利用钱德拉x光天文台,结合名为微透镜的行星探测技术,发现了遥远星系中行星存在的证据,称“其中一些系外行星相对而言和月球一样小,而另一些则和木星一样大。与地球不同,大多数系外行星与恒星没有紧密的联系,所以它们实际上是在太空中漫游或者在恒星之间松散地轨道运行。我们可以估计这个遥远的星系中的行星数量超过一万亿颗。[18]

2.1 早期推测

十六世纪意大利哲学家乔尔丹诺·布鲁诺是哥白尼太阳中心主义理论的早期支持者,此理论主张地球和其他行星围绕太阳运行,乔尔丹诺提出了恒星与太阳相似并且同样被行星伴随的观点。

在十八世纪,艾萨克·牛顿在《学者总论》中也提到了同样的可能性原理。在与太阳的行星进行比较时,他写道,“如果固定恒星是相似系统的中心,恒星都将按照相似的布局建造,并受制于其中心。"[19]

1952年,也就是第一颗热木星被发现的40多年前,奥托·斯特鲁维写道,没有令人信服的理由说明为什么行星不能比太阳系更靠近它们的母星,并提出利用多普勒光谱学和过境测光方法可以探测短轨道的超级木星。[20]

2.2 不可信的主张

自十九世纪以来,就有人声称探测到了太阳系外行星。一些最早的主张涉及双星70蛇夫座。1855年,东印度公司马德拉斯天文台的威廉·斯蒂芬·雅各布报告称,轨道异常使得这个系统中极有可能存在行星体。[21]19世纪90年代,芝加哥大学和美国海军天文台的托马斯·塞伊指出,轨道异常证明了70蛇夫座系统中存在暗体,围绕其中一颗恒星的运行周期是36年。[22]然而,林雷·莫尔顿发表了一篇论文,证明一个具有这些轨道参数的三体系统是高度不稳定的。[23]在20世纪50年代和60年代,斯沃斯莫尔学院的彼得·范·德·坎普提出了另一系列著名的探测主张,这次是针对围绕巴纳德星运行的行星。[24]天文学家现在普遍认为所有早期的探测报告都是错误的。[25]

1991年,安德鲁·琳恩、贝利斯和谢马尔声称他们利用了用脉冲星时间差,在PSR 1829-10的轨道上发现了一颗脉冲星行星。[26]这一说法一度受到强烈关注,但琳恩和他的团队很快收回了这一说法。[27]

2.3 被证实的发现

截止至2019年12月,共3433个已确认的系外行星在太阳系外行星百科全书被列出,包括几个自20世纪80年代末以来备受争议的主张被确认。1988年,来自维多利亚大学及不列颠哥伦比亚大学的加拿大天文学家布鲁斯·坎贝尔、沃克和杨斯蒂芬森,首次发表了他们的发现,并获得了后续的证实。[28]尽管他们对声称有行星探测持谨慎态度,但是他们的径向速度观测表明,一颗行星围绕伽马星Cephei运行。天文学家多年后仍对这一观测和其他类似的观测结果持疑态度,部分原因是当时这些观测处于仪器能力的极限。人们认为一些明显的行星可能是棕矮星,质量介于行星和恒星之间的物体。1990年发表了更多的观测结果,支持了绕伽马星轨道运行的行星的存在,[29]但是1992年的后续工作再次引起了严重的怀疑。[30]最后,在2003年,改进的科技使得行星的存在得以证实。[31]

1992年1月9日,射电天文学家亚历山大·沃尔兹森和戴尔·弗莱奥宣布发现两颗围绕脉冲星PSR 1257+12运行的行星。[17]这一发现得到了证实,并被普遍认为是第一次对系外行星的明确探测。后续的观察巩固了这些结果,1994年对第三颗行星的确认在大众媒体上重新引发了这个话题。[32]这些脉冲星行星被认为是在第二轮行星形成中,由产生脉冲星的超新星的不寻常的残余物形成的,或者其他是气态巨行星剩余的岩石核心,它们以某种方式幸存于超新星,然后衰变到它们当前的轨道。

1995年10月6日,日内瓦大学的米歇尔·马约尔和迪迪埃·奎罗兹宣布首次明确探测到一颗绕主序列恒星运行的系外行星,即是附近的G型恒星51 Pegasi。[33][34]这一发现是在上普罗旺斯天文台做出的,开启了外行星探索的新时代。技术的进步,尤其是高分辨率光谱学的进步,促使了许多新的系外行星被更快地探测:天文学家可以通过测量行星对宿主恒星运动的重力影响来间接探测系外行星。更多太阳系外的行星随后通过观察一颗绕轨道运行的行星在恒星前方经过时,恒星的视星等变化量而被发现。

最初,大多数已知的系外行星都是质量很大的行星,其轨道非常靠近它们的母星。天文学家对这些“热木星”感到惊讶,因为行星形成的理论表明,巨型行星应该只在离恒星很远的地方形成。但是最终发现了更多其他种类的行星,现在人们明白热木星只构成了系外行星的少数。1999年,乌斯隆·仙女座成为第一颗已知有多个行星的主序恒星。[35]开普勒-16号包含了第一颗被发现围绕双星系统运行的行星。[36]

2014年2月26日,美国国家航空航天局宣布发现了715颗被新验证的系外行星,利用开普勒太空望远镜。这些系外行星是用一种叫做“多重性验证”的统计技术来检查的。[37][38][39]在这些结果之前,大多数被证实的行星都是气体巨行星,其大小与木星相当或更大,因为它们更容易被探测到,但是开普勒行星的尺寸大多介于海王星和地球之间。[37]

2015年7月23日,美国国家航空航天局公布了开普勒-452b,一颗接近地球大小的行星,围绕G2型恒星的可居住区运行。[40]

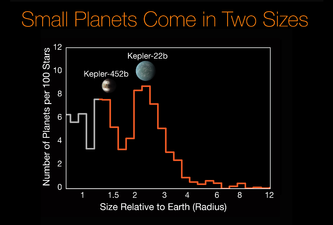

2018年9月6日,美国国家航空航天局在处女座发现了一颗距地球约145光年的外行星。[41]这颗系外行星沃尔夫503b是地球的两倍大,被发现时围绕着一种被称为“橙色矮星”的恒星。沃尔夫503b由于离恒星很近,在短短六天内完成了一个轨道运行。这颗系外行星相对靠近地球,它的主星闪耀着极其明亮的光芒。在所谓的富尔顿间隙附近,沃尔夫503b是唯一能被发现的非常大的系外行星。富尔顿间隙在2017年首次被注意到的,即在一定质量范围内行星是很难被观测到的。[42][41]

研究系外行星的天文学家已经在我们的星系中发现了数以千计的系外行星。沃尔夫503b至关重要,因为它离地球很近,便于通过开普勒太空望远镜做更多的拓展研究。沃尔夫503b绕轨道运行的“橙色矮星”是一颗明亮的恒星。科学家称橙色矮星寿命比太阳长三倍。沃尔夫503b对它的橙色矮星有很大的影响。由于沃尔夫503b的尺寸很大,沃尔夫503b对它的主星有引力影响。富尔顿间隙研究为天文学家开辟了一个新的领域,天文学家仍在研究富尔顿间隙中被发现的行星是气态的还是岩石状的。[41]

2.4 候选的发现

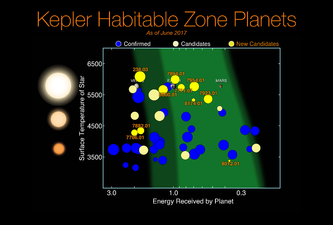

截至2017年6月,美国国家航空航天局的开普勒任务已经识别了5000多颗行星候选,[43]其中一些接近地球大小,位于可居住区,一些在类太阳恒星周围。[44][45][46]

3 方法学编辑

在所有已确认的系外行星中,约97%是通过间接探测技术发现的,主要是利用径向速度测量和过境测光技术。

4 形成和进化编辑

行星可能在恒星形成的几到几千万(或更多)年内形成。[49][50][51][52][53]太阳系的行星只能在它们目前的状态下被观察到,但是通过对不同年龄的不同行星系统进行观察,允许我们观察到处于不同进化阶段的行星。可得的观测范围从仍在形成初期原行星盘[54]的行星,到超过几十亿年的行星。[55]当行星形成气态原行星盘时,[56]它们聚集氢或氦包层。[57][58]随着时间的推移,这些包层会依照行星的质量冷却和收缩,部分甚至全部氢或氦最终消失在太空中。[56]这意味着即使是类地行星,如果它们形成得足够早,也可能以大半径开始。[59][60][61]开普勒-51b就是一个例子,它的质量只有地球的两倍,但几乎是土星的大小,然而土星的质量是地球质量的一百倍。开普勒-51b在几亿年前还很年轻。[62]

4.1 离心率

在已被发现的许多系外行星中,大多数都比太阳系中的行星有更高的轨道离心率。在圆形轨道附近发现的轨道偏心率低的系外行星,几乎都非常靠近它们的恒星,并且潮汐锁定在恒星上。相比之下,太阳系里的八颗行星中有七颗行星的轨道接近圆形。已被发现的系外行星表明,偏心率异常低的太阳系是罕见的。[63]一种理论将这种低离心率归因于太阳系中行星的数量众多;另一种理论认为它的出现是因为太阳系独特的小行星带。人们已经发现了其他一些存在多行星的星系,但没有一个与太阳系类似。太阳系有独特的星子系统,使得行星的轨道接近圆形。发现的系外行星系统要么没有星子系统,要么是星子系统过大。宜居性需要低离心率,尤其是高级生命。[64]高度多样性的行星系统更有可能拥有可居住的系外行星。[65][66]

5 行星寄宿恒星编辑

每颗恒星平均至少有一颗行星。[67]大约五分之一的类太阳恒星有一个地球大小的可居住区的行星。[67]

大多数已知的系外行星围绕着与太阳大致相似的恒星运行,即光谱类别为F、G或K的主序列恒星。较低质量的恒星,比如光谱类别为M的红矮星,不太可能拥有足够大的行星,可以通过径向速度方法被探测到。[67][68]尽管如此,科学家们还是利用开普勒宇宙飞船发现了红矮星周围的几十颗行星,开普勒宇宙飞船使用传输方法探测较小的行星。

使用来自开普勒的数据,人们已经发现恒星的金属性和恒星拥有行星的概率之间存在关联。金属含量较高的恒星比金属含量较低的恒星更有可能拥有行星,尤其是巨型行星。[69]

一些行星围绕双星系统的一颗恒星运行;[70]已发现的一些环联星运转行星,它们围绕双星的两颗恒星运行。已知有几颗行星在三星系统中[71] ,以及有一颗行星在开普勒-64四星系统中。

6 普遍特征编辑

6.1 颜色和亮度

2013年,系外行星的颜色首次被确定。高清189733b的最佳反照率测量显示它是深蓝色。[72][73]同年晚些时候,其他几颗系外行星的颜色被确定,包括视觉上呈洋红色的GJ 504 b,[74]以及近距离观察呈现微红的卡帕仙女座菌株b。[75]

一颗行星的表观亮度(表现幅度),取决于观察者的距离远近、该行星的反照率大小以及该行星从其恒星接收到的光量。接收到的光亮取决于该行星离恒星有多远,以及该恒星有多亮。因此,一颗接近恒星的低反照率行星可能比远离恒星的高反照率行星看起来更亮。[76]

就几何反照率而言,已知最暗的行星是TrES-2b,这是一颗热木星,它反射的光不到其恒星发出光的1%,这使得它的反射性不如煤或黑色丙烯酸涂料。由于大气中的钠和钾,热木星预计会相当暗,但TrES-2b如此暗的原因还未知——可能是由于一种未知的化合物。[77][78][79]

对于气态巨行星来说,几何反照率通常随着金属含量或大气温度的升高而降低,除非有云来改变这种效应。云柱深度的增加会增加光学波长的反照率,但会降低特定的红外波长的反照率。光学反照率随着时间的推移而增加,因为较古老的行星有较高的云柱深度。光学反照率随着质量的增加而降低,因为质量较高的巨型行星具有更高的表面引力,这就产生了较低的云柱深度。此外,椭圆轨道会引起大气成分的重大波动,这可能会产生重大影响。[80]

对于大质量或初期的气态巨行星来说,在某些近红外波长下,热辐射比反射多。因此,尽管光学亮度完全依赖于行星的时期,但在近红外波长下并非总是如此。[80]

气态巨行星的温度随着时间的推移和离恒星的距离而降低。即使没有云,降低温度也会增加光学反照率。在足够低的温度下,水云形成,进一步增加了光学反照率。在更低的温度下,氨云形成,在大多数光学和近红外波长下导致最高的反照率。[80]

6.2 磁场

2014年,HD 209458 b周围的磁场是通过氢从地球蒸发的方式推断出来的。这是首次间接探测到太阳系外行星上的磁场。HD 209458 b的磁场强度估计约为木星磁场的十分之一。[81][82]

太阳系外行星的磁场可以通过它们的极光射电辐射探测到,而这些射电辐射可以被足够灵敏的射电望远镜探测到,比如LOFAR。[83][84]无线电发射能够确定外行星内部的旋转速度,并且可以产生测量外行星旋转的方法,相比测量云的运动更精确。[85]

地球磁场是由流动的液态金属核产生的,但在高压的巨大超级地球中,可能会形成不同的化合物,这些化合物与地球条件下产生的化合物不同。化合物可能会形成更高的黏滞性和熔解温度,这可能会阻止内部分离成不同的层,从而导致未分化的无核地幔。有些氧化镁的形式,比如MgSi3O12,在超级地球的压力和温度下可能是液态金属,并可能在超级地球的地幔中产生磁场。[86][87]

据观察,热木星的半径比预期的要大。这可能是由恒星风和行星磁气圈之间的相互作用引起的,这种相互作用产生了一股流经行星的电流,该电流加热了行星,导致其膨胀。恒星的磁性越强,恒星风就越大,电流就越大,导致行星的更多加热和膨胀。这个理论支持了恒星活动与膨胀的行星半径相关的观察。[88]

2018年8月,科学家宣布将气态氘转化为液态金属。这可能有助于研究人员更好地理解气态巨行星,如木星、土星和相关的系外行星,因为这些行星被认为含有大量液态金属氢,这可能是它们被观测到有强大磁场的原因。[89][90]

尽管科学家此前宣布,靠近的系外行星的磁场可能会导致宿主恒星上恒星耀斑和恒星斑点的增加,但在2019年,这一说法在HD 189733系统中被证明是错误的。在被研究透彻的HD 189733系统中,未能检测到“恒星-行星相互作用”,这使其他相关的效应声明受到质疑。[91]

6.3 板块构造论

2007年,两个独立的研究小组对大型超级地球板块构造的可能性得出了相反的结论,[92][93]其中一个团队说板块构造将是间歇性的或停滞的,[94]另一个团队说,即使地球干燥,板块构造也很可能在超级地球上发生。[95]

如果超级地球的水比地球多80倍,那么它们就变成了海洋行星,所有的陆地都被完全淹没了。然而,如果水少于这个极限,那么深水循环将在海洋和地幔之间移动足够的水,使大陆得以存在。[96][97]

6.4 火山作用

坎昆55号的地表温度变化很大,这归因于火山活动可能释放出覆盖行星并阻挡热辐射的大量尘埃云。[98][99]

6.5 环带

恒星1SWAP j 140747.93-394542.6被一个比土星环大得多的环带系统中的物体所环绕。然而,物体的质量是未知的;它可能是褐矮星或低质量恒星,而不是行星。[100][101]

Fomalhaut b的光学图像亮度可能是由于星光反射出的环行星环系统的半径是木星半径的20到40倍,大约相当于伽利略卫星的轨道大小。[102]

太阳系气态巨行星的环与它们所在行星的赤道对齐。然而,对于围绕恒星运行的系外行星来说,来自恒星的潮汐力会导致行星的最外环与行星围绕恒星的轨道平面对齐。行星的最内环仍然会与行星的赤道对齐,因此如果行星有一个倾斜的旋转轴,那么内环和外环之间的不同会产生一个扭曲的环系统。[103]

6.6 卫星

2013年12月,一颗流浪行星的候选系外卫星被宣布。[104]2018年10月3日,有证据表明开普勒-1625b轨道上有一个大的系外卫星。[105]

6.7 大气

在几颗系外行星周围已经探测到大气层。最先被观察到的是2001年的HD 209458 b。[106]

KIC 12557548 b是一颗小的岩石行星,非常靠近它的恒星,像彗星一样蒸发并留下云和尘埃的尾部。[107]尘埃可能是火山喷发出来的灰烬,由于这颗小行星的低表面重力而漏出,也可能是由于金属因离恒星如此之近而被高温蒸发,气化的金属随后凝结成灰尘。[108]

2015年6月,科学家报告指出,GJ 436 b的大气正在蒸发,导致行星周围出现巨大的云,并且由于宿主恒星的辐射,形成一条 14×106 km (9×106 mi)长的拖尾。[109]

2017年5月,来自地球的闪光被发现是来自大气中冰晶的反射光,看起来像来自一百万英里外的轨道卫星的闪光。[110][111]用来确定这一点的技术可能对研究更遥远的大气有用,包括系外行星的大气。

6.8 日照模式

在1:1自旋轨道共振中潮汐锁定的行星会让它们的恒星总是直接在头顶上的一个点上发光,这个点会很热,而相对的半球却没有光,而且非常冷。这样一个星球可能类似于一个眼球,热点是瞳孔。[112]轨道偏心的行星可能被锁定在其他共振中。3:2和5:2共振会导致双眼球模式,在东半球和西半球都有热点。[113]既有偏心轨道又有倾斜旋转轴的行星会有更复杂的日照模式。[114]

随着更多的行星被发现,外行星学领域继续发展成为对太阳系外的世界的更深入研究,并将最终发展到研究太阳系以外行星上的生命。[115]在宇宙距离上,生命只有在行星尺度上进化并强烈改变了行星环境的情况下才能被探测到,这种改变不能用经典的物理化学平衡过程来解释。[115]例如,氧分子(O2)在地球大气层中是活的植物和多种微生物光合作用的结果,因此它可以是系外行星上生命的迹象,尽管少量氧气也可以通过非生物手段产生。[115]此外,一颗潜在的可居住行星必须围绕一颗稳定的恒星运行一段距离,在这段距离内,具有足够大气压力的行星质量物体可以在其表面支撑液态水。[116][117]

7 笔记编辑

- For the purpose of this 1 in 5 statistic, "Sun-like" means G-type star. Data for Sun-like stars was not available so this statistic is an extrapolation from data about K-type stars

- For the purpose of this 1 in 5 statistic, Earth-sized means 1–2 Earth radii

- For the purpose of this 1 in 5 statistic, "habitable zone" means the region with 0.25 to 4 times Earth's stellar flux (corresponding to 0.5–2 AU for the Sun).

- About 1/4 of stars are GK Sun-like stars. The number of stars in the galaxy is not accurately known, but assuming 200 billion stars in total, the Milky Way would have about 50 billion Sun-like (GK) stars, of which about 1 in 5 (22%) or 11 billion would be Earth-sized in the habitable zone. Including red dwarfs would increase this to 40 billion.

参考文献

- [1]

^"exoplanet Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary"..

- [2]

^F. J. Ballesteros; A. Fernandez-Soto; V. J. Martinez (2019). "Title: Diving into Exoplanets: Are Water Seas the Most Common?". Astrobiology. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1720..

- [3]

^Sanders, R. (4 November 2013). "Astronomers answer key question: How common are habitable planets?". newscenter.berkeley.edu..

- [4]

^Khan, Amina (4 November 2013). "Milky Way may host billions of Earth-size planets". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 November 2013..

- [5]

^"HR 2562 b". Caltech. Retrieved 15 February 2018..

- [6]

^Konopacky, Quinn M.; Rameau, Julien; Duchêne, Gaspard; Filippazzo, Joseph C.; Giorla Godfrey, Paige A.; Marois, Christian; Nielsen, Eric L. (20 September 2016). "Discovery of a Substellar Companion to the Nearby Debris Disk Host HR 2562" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 829 (1): 10. arXiv:1608.06660. Bibcode:2016ApJ...829L...4K. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/829/1/L4..

- [7]

^Bodenheimer, P.; D'Angelo, G.; Lissauer, J. J.; Fortney, J. J.; et al. (2013). "Deuterium Burning in Massive Giant Planets and Low-mass Brown Dwarfs Formed by Core-nucleated Accretion". The Astrophysical Journal. 770 (2): 120 (13 pp.). arXiv:1305.0980. Bibcode:2013ApJ...770..120B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/770/2/120..

- [8]

^Zachos, Elaine (5 February 2018). "More Than a Trillion Planets Could Exist Beyond Our Galaxy – A new study gives the first evidence that exoplanets exist beyond the Milky Way". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 5 February 2018..

- [9]

^Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (5 February 2018). "Scientists Find Evidence of Thousands of Planets in Distant Galaxy". Gizmodo. Retrieved 5 February 2018..

- [10]

^Anglada-Escudé, Guillem; Amado, Pedro J.; Barnes, John; Berdiñas, Zaira M.; Butler, R. Paul; Coleman, Gavin A. L.; de la Cueva, Ignacio; Dreizler, Stefan; Endl, Michael (25 August 2016). "A terrestrial planet candidate in a temperate orbit around Proxima Centauri". Nature (in 英语). 536 (7617): 437–440. arXiv:1609.03449. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..437A. doi:10.1038/nature19106. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 27558064..

- [11]

^Overbye, Dennis (6 January 2015). "As Ranks of Goldilocks Planets Grow, Astronomers Consider What's Next". The New York Times..

- [12]

^Beichman, C.; Gelino, Christopher R.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Cushing, Michael C.; Dodson-Robinson, Sally; Marley, Mark S.; Morley, Caroline V.; Wright, E. L. (2014). "WISE Y Dwarfs As Probes of the Brown Dwarf-Exoplanet Connection". The Astrophysical Journal. 783 (2): 68. arXiv:1401.1194. Bibcode:2014ApJ...783...68B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/783/2/68..

- [13]

^Neil DeGrasse Tyson in Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey as referred to by National Geographic.

- [14]

^Strigari, L. E.; Barnabè, M.; Marshall, P. J.; Blandford, R. D. (2012). "Nomads of the Galaxy". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 423 (2): 1856–1865. arXiv:1201.2687. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.423.1856S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21009.x. estimates 700 objects >10−6 solar masses (roughly the mass of Mars) per main-sequence star between 0.08 and 1 Solar mass, of which there are billions in the Milky Way..

- [15]

^"International Astronomical Union | IAU". www.iau.org. Retrieved 29 January 2017..

- [16]

^"1992 --"The Year the Milky Way's Planets Came to Life"" (in English). Daily Galaxy. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link).

- [17]

^Landau, Elizabeth (12 November 2017). "Overlooked Treasure: The First Evidence of Exoplanets". NASA. Retrieved 1 November 2017..

- [18]

^"These May Be the First Planets Found Outside Our Galaxy". National Geographic. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2018..

- [19]

^Newton, Isaac; I. Bernard Cohen; Anne Whitman (1999) [1713]. The Principia: A New Translation and Guide. University of California Press. p. 940. ISBN 978-0-520-08816-0..

- [20]

^Struve, Otto (1952). "Proposal for a project of high-precision stellar radial velocity work". The Observatory. 72: 199–200. Bibcode:1952Obs....72..199S..

- [21]

^Jacob, W. S. (1855). "On Certain Anomalies presented by the Binary Star 70 Ophiuchi". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 15 (9): 228–230. Bibcode:1855MNRAS..15..228J. doi:10.1093/mnras/15.9.228..

- [22]

^See, T. J. J. (1896). "Researches on the orbit of 70 Ophiuchi, and on a periodic perturbation in the motion of the system arising from the action of an unseen body". The Astronomical Journal. 16: 17–23. Bibcode:1896AJ.....16...17S. doi:10.1086/102368..

- [23]

^Sherrill, T. J. (1999). "A Career of Controversy: The Anomaly of T. J. J. See" (PDF). Journal for the History of Astronomy. 30 (98): 25–50. Bibcode:1999JHA....30...25S. doi:10.1177/002182869903000102..

- [24]

^van de Kamp, P. (1969). "Alternate dynamical analysis of Barnard's star". Astronomical Journal. 74: 757–759. Bibcode:1969AJ.....74..757V. doi:10.1086/110852..

- [25]

^Boss, Alan (2009). The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets. Basic Books. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-465-00936-7..

- [26]

^Bailes, M.; Lyne, A. G.; Shemar, S. L. (1991). "A planet orbiting the neutron star PSR1829–10". Nature. 352 (6333): 311–313. Bibcode:1991Natur.352..311B. doi:10.1038/352311a0..

- [27]

^Lyne, A. G.; Bailes, M. (1992). "No planet orbiting PS R1829–10". Nature. 355 (6357): 213. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..213L. doi:10.1038/355213b0..

- [28]

^Campbell, B.; Walker, G. A. H.; Yang, S. (1988). "A search for substellar companions to solar-type stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 331: 902. Bibcode:1988ApJ...331..902C. doi:10.1086/166608..

- [29]

^Lawton, A. T.; Wright, P. (1989). "A planetary system for Gamma Cephei?". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 42: 335–336. Bibcode:1989JBIS...42..335L..

- [30]

^Walker, G. A. H; Bohlender, D. A.; Walker, A. R.; Irwin, A. W.; Yang, S. L. S.; Larson, A. (1992). "Gamma Cephei – Rotation or planetary companion?". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 396 (2): L91–L94. Bibcode:1992ApJ...396L..91W. doi:10.1086/186524..

- [31]

^Hatzes, A. P.; Cochran, William D.; Endl, Michael; McArthur, Barbara; Paulson, Diane B.; Walker, Gordon A. H.; Campbell, Bruce; Yang, Stephenson (2003). "A Planetary Companion to Gamma Cephei A". Astrophysical Journal. 599 (2): 1383–1394. arXiv:astro-ph/0305110. Bibcode:2003ApJ...599.1383H. doi:10.1086/379281..

- [32]

^Holtz, Robert (22 April 1994). "Scientists Uncover Evidence of New Planets Orbiting Star". Los Angeles Times via The Tech Online..

- [33]

^Mayor, M.; Queloz, D. (1995). "A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star". Nature. 378 (6555): 355–359. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..355M. doi:10.1038/378355a0..

- [34]

^Gibney, Elizabeth (18 December 2013). "In search of sister earths". Nature. 504 (7480): 357–65. Bibcode:2013Natur.504..357.. doi:10.1038/504357a. PMID 24352276..

- [35]

^Lissauer, J. J. (1999). "Three planets for Upsilon Andromedae". Nature. 398 (6729): 659. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..659L. doi:10.1038/19409..

- [36]

^Doyle, L. R.; Carter, J. A.; Fabrycky, D. C.; Slawson, R. W.; Howell, S. B.; Winn, J. N.; Orosz, J. A.; Prša, A.; Welsh, W. F.; Quinn, S. N.; Latham, D.; Torres, G.; Buchhave, L. A.; Marcy, G. W.; Fortney, J. J.; Shporer, A.; Ford, E. B.; Lissauer, J. J.; Ragozzine, D.; Rucker, M.; Batalha, N.; Jenkins, J. M.; Borucki, W. J.; Koch, D.; Middour, C. K.; Hall, J. R.; McCauliff, S.; Fanelli, M. N.; Quintana, E. V.; Holman, M. J.; et al. (2011). "Kepler-16: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet". Science. 333 (6049): 1602–6. arXiv:1109.3432. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1602D. doi:10.1126/science.1210923. PMID 21921192..

- [37]

^Johnson, Michele; Harrington, J.D. (26 February 2014). "NASA's Kepler Mission Announces a Planet Bonanza, 715 New Worlds". NASA. Retrieved 26 February 2014..

- [38]

^Wall, Mike (26 February 2014). "Population of Known Alien Planets Nearly Doubles as NASA Discovers 715 New Worlds". space.com. Retrieved 27 February 2014..

- [39]

^Jonathan Amos (26 February 2014). "Kepler telescope bags huge haul of planets". BBC News. Retrieved 27 February 2014..

- [40]

^Johnson, Michelle; Chou, Felicia (23 July 2015). "NASA's Kepler Mission Discovers Bigger, Older Cousin to Earth". NASA..

- [41]

^NASA. "Discovery alert! Oddball planet could surrender its secrets". Exoplanet Exploration: Planets Beyond our Solar System. Retrieved 28 November 2018..

- [42]

^"Solarsystemquick.com: Solar System Facts – Facts About the Solar System". www.solarsystemquick.com. Retrieved 28 November 2018..

- [43]

^Johnson, Michele (9 June 2017). "Media Invited to NASA's Kepler Science Conference". NASA. Retrieved 20 June 2017..

- [44]

^Jerry Colen (4 November 2013). "Kepler". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013..

- [45]

^Harrington, J. D.; Johnson, M. (4 November 2013). "NASA Kepler Results Usher in a New Era of Astronomy"..

- [46]

^"NASA's Exoplanet Archive KOI table". NASA. Retrieved 28 February 2014..

- [47]

^Lewin, Sarah (19 June 2017). "NASA's Kepler Space Telescope Finds Hundreds of New Exoplanets, Boosts Total to 4,034". NASA. Retrieved 19 June 2017..

- [48]

^Overbye, Dennis (19 June 2017). "Earth-Size Planets Among Final Tally of NASA's Kepler Telescope". The New York Times..

- [49]

^Mamajek, Eric E.; Usuda, Tomonori; Tamura, Motohide; Ishii, Miki (2009). "Initial Conditions of Planet Formation: Lifetimes of Primordial Disks". AIP Conference Proceedings. Exoplanets and Disks: Their Formation and Diversity: Proceedings of the International Conference. 1158. p. 3. arXiv:0906.5011. Bibcode:2009AIPC.1158....3M. doi:10.1063/1.3215910..

- [50]

^Rice, W. K. M.; Armitage, P. J. (2003). "On the Formation Timescale and Core Masses of Gas Giant Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 598 (1): L55–L58. arXiv:astro-ph/0310191. Bibcode:2003ApJ...598L..55R. doi:10.1086/380390..

- [51]

^Yin, Q.; Jacobsen, S. B.; Yamashita, K.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Télouk, P.; Albarède, F. (2002). "A short timescale for terrestrial planet formation from Hf–W chronometry of meteorites". Nature. 418 (6901): 949–952. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..949Y. doi:10.1038/nature00995. PMID 12198540..

- [52]

^D'Angelo, G.; Durisen, R. H.; Lissauer, J. J. (2011). "Giant Planet Formation". In S. Seager. Exoplanets. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ. pp. 319–346. arXiv:1006.5486. Bibcode:2010exop.book..319D..

- [53]

^D'Angelo, G.; Lissauer, J. J. (2018). "Formation of Giant Planets". In Deeg H., Belmonte J. Handbook of Exoplanets. Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature. pp. 2319–2343. arXiv:1806.05649. Bibcode:2018haex.bookE.140D. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55333-7_140. ISBN 978-3-319-55332-0..

- [54]

^Calvet, Nuria; D'Alessio, Paola; Hartmann, Lee; Wilner, David; Walsh, Andrew; Sitko, Michael (2001). "Evidence for a developing gap in a 10 Myr old protoplanetary disk". The Astrophysical Journal. 568 (2): 1008–1016. arXiv:astro-ph/0201425. Bibcode:2002ApJ...568.1008C. doi:10.1086/339061..

- [55]

^Fridlund, Malcolm; Gaidos, Eric; Barragán, Oscar; Persson, Carina; Gandolfi, Davide; Cabrera, Juan; Hirano, Teruyuki; Kuzuhara, Masayuki; Csizmadia, Sz; Nowak, Grzegorz; Endl, Michael; Grziwa, Sascha; Korth, Judith; Pfaff, Jeremias; Bitsch, Bertram; Johansen, Anders; Mustill, Alexander; Davies, Melvyn; Deeg, Hans; Palle, Enric; Cochran, William; Eigmüller, Philipp; Erikson, Anders; Guenther, Eike; Hatzes, Artie; Kiilerich, Amanda; Kudo, Tomoyuki; MacQueen, Philipp; Narita, Norio; Nespral, David; Pätzold, Martin; Prieto-Arranz, Jorge; Rauer, Heike; van Eylen, Vincent (28 April 2017). "EPIC210894022b −A short period super-Earth transiting a metal poor, evolved old star". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 604: A16. arXiv:1704.08284. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201730822..

- [56]

^D'Angelo, G.; Bodenheimer, P. (2016). "In Situ and Ex Situ Formation Models of Kepler 11 Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 828 (1): id. 33 (32 pp.). arXiv:1606.08088. Bibcode:2016ApJ...828...33D. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/828/1/33..

- [57]

^D'Angelo, G.; Bodenheimer, P. (2013). "Three-Dimensional Radiation-Hydrodynamics Calculations of the Envelopes of Young Planets Embedded in Protoplanetary Disks". The Astrophysical Journal. 778 (1): 77 (29 pp.). arXiv:1310.2211. Bibcode:2013ApJ...778...77D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/778/1/77..

- [58]

^D'Angelo, G.; Weidenschilling, S. J.; Lissauer, J. J.; Bodenheimer, P. (2014). "Growth of Jupiter: Enhancement of core accretion by a voluminous low-mass envelope". Icarus. 241: 298–312. arXiv:1405.7305. Bibcode:2014Icar..241..298D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.06.029..

- [59]

^Lammer, H.; Stokl, A.; Erkaev, N. V.; Dorfi, E. A.; Odert, P.; Gudel, M.; Kulikov, Y. N.; Kislyakova, K. G.; Leitzinger, M. (2014). "Origin and loss of nebula-captured hydrogen envelopes from 'sub'- to 'super-Earths' in the habitable zone of Sun-like stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 439 (4): 3225–3238. arXiv:1401.2765. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.439.3225L. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu085..

- [60]

^Johnson, R. E. (2010). "Thermally-Diven Atmospheric Escape". The Astrophysical Journal. 716 (2): 1573–1578. arXiv:1001.0917. Bibcode:2010ApJ...716.1573J. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/716/2/1573..

- [61]

^Zendejas, J.; Segura, A.; Raga, A.C. (2010). "Atmospheric mass loss by stellar wind from planets around main sequence M stars". Icarus. 210 (2): 539–544. arXiv:1006.0021. Bibcode:2010Icar..210..539Z. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.07.013..

- [62]

^Masuda, K. (2014). "Very Low Density Planets Around Kepler-51 Revealed with Transit Timing Variations and an Anomaly Similar to a Planet-Planet Eclipse Event". The Astrophysical Journal. 783 (1): 53. arXiv:1401.2885. Bibcode:2014ApJ...783...53M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/783/1/53..

- [63]

^exoplanets.org, ORBITAL ECCENTRICITES, by G.Marcy, P.Butler, D.Fischer, S.Vogt, 20 Sept 2003.

- [64]

^Ward, Peter; Brownlee, Donald (2000). Rare Earth: Why Complex Life is Uncommon in the Universe. Springer. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-0-387-98701-9..

- [65]

^Limbach, MA; Turner, EL (2015). "Exoplanet orbital eccentricity: multiplicity relation and the Solar System". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112 (1): 20–4. arXiv:1404.2552. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112...20L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1406545111. PMC 4291657. PMID 25512527..

- [66]

^Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Planetesimals in Debris Disks, by Andrew N. Youdin and George H. Rieke, 2015.

- [67]

^Cassan, A.; Kubas, D.; Beaulieu, J. -P.; Dominik, M.; Horne, K.; Greenhill, J.; Wambsganss, J.; Menzies, J.; Williams, A.; Jørgensen, U. G.; Udalski, A.; Bennett, D. P.; Albrow, M. D.; Batista, V.; Brillant, S.; Caldwell, J. A. R.; Cole, A.; Coutures, C.; Cook, K. H.; Dieters, S.; Prester, D. D.; Donatowicz, J.; Fouqué, P.; Hill, K.; Kains, N.; Kane, S.; Marquette, J. -B.; Martin, R.; Pollard, K. R.; Sahu, K. C. (11 January 2012). "One or more bound planets per Milky Way star from microlensing observations". Nature. 481 (7380): 167–169. arXiv:1202.0903. Bibcode:2012Natur.481..167C. doi:10.1038/nature10684. PMID 22237108..

- [68]

^Bonfils, X.; Forveille, T.; Delfosse, X.; Udry, S.; Mayor, M.; Perrier, C.; Bouchy, F.; Pepe, F.; Queloz, D.; Bertaux, J. -L. (2005). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 443 (3): L15–L18. arXiv:astro-ph/0509211. Bibcode:2005A&A...443L..15B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500193..

- [69]

^Wang, J.; Fischer, D. A. (2014). "Revealing a Universal Planet–Metallicity Correlation for Planets of Different Solar-Type Stars". The Astronomical Journal. 149 (1): 14. arXiv:1310.7830. Bibcode:2015AJ....149...14W. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/149/1/14..

- [70]

^Schwarz, Richard. Binary Catalogue of Exoplanets. Universität Wien.

- [71]

^Schwarz, Richard. STAR-DATA. Universität Wien.

- [72]

^NASA Hubble Finds a True Blue Planet. NASA. 11 July 2013.

- [73]

^Evans, T. M.; Pont, F. D. R.; Sing, D. K.; Aigrain, S.; Barstow, J. K.; Désert, J. M.; Gibson, N.; Heng, K.; Knutson, H. A.; Lecavelier Des Etangs, A. (2013). "The Deep Blue Color of HD189733b: Albedo Measurements with Hubble Space Telescope/Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph at Visible Wavelengths". The Astrophysical Journal. 772 (2): L16. arXiv:1307.3239. Bibcode:2013ApJ...772L..16E. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/772/2/L16..

- [74]

^Kuzuhara, M.; Tamura, M.; Kudo, T.; Janson, M.; Kandori, R.; Brandt, T. D.; Thalmann, C.; Spiegel, D.; Biller, B.; Carson, J.; Hori, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Burrows, A.; Henning, T.; Turner, E. L.; McElwain, M. W.; Moro-Martín, A.; Suenaga, T.; Takahashi, Y. H.; Kwon, J.; Lucas, P.; Abe, L.; Brandner, W.; Egner, S.; Feldt, M.; Fujiwara, H.; Goto, M.; Grady, C. A.; Guyon, O.; Hashimoto, J.; et al. (2013). "Direct Imaging of a Cold Jovian Exoplanet in Orbit around the Sun-like Star GJ 504" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 774 (11): 11. arXiv:1307.2886. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774...11K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/774/1/11..

- [75]

^Carson; Thalmann; Janson; Kozakis; Bonnefoy; Biller; Schlieder; Currie; McElwain (15 November 2012). "Direct Imaging Discovery of a 'Super-Jupiter' Around the late B-Type Star Kappa And". The Astrophysical Journal. 763 (2): L32. arXiv:1211.3744. Bibcode:2013ApJ...763L..32C. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/763/2/L32..

- [76]

^The Apparent Brightness and Size of Exoplanets and their Stars, Abel Mendez, updated 30 June 2012, 12:10 pm.

- [77]

^"Coal-Black Alien Planet Is Darkest Ever Seen". Space.com. Retrieved 12 August 2011..

- [78]

^Kipping, David M.; Spiegel, David S. (2011). "Detection of visible light from the darkest world". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 417 (1): L88–L92. arXiv:1108.2297. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.417L..88K. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2011.01127.x..

- [79]

^Barclay, T.; Huber, D.; Rowe, J. F.; Fortney, J. J.; Morley, C. V.; Quintana, E. V.; Fabrycky, D. C.; Barentsen, G.; Bloemen, S.; Christiansen, J. L.; Demory, B. O.; Fulton, B. J.; Jenkins, J. M.; Mullally, F.; Ragozzine, D.; Seader, S. E.; Shporer, A.; Tenenbaum, P.; Thompson, S. E. (2012). "Photometrically derived masses and radii of the planet and star in the TrES-2 system". The Astrophysical Journal. 761 (1): 53. arXiv:1210.4592. Bibcode:2012ApJ...761...53B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/761/1/53..

- [80]

^Burrows, Adam (2014). "Scientific Return of Coronagraphic Exoplanet Imaging and Spectroscopy Using WFIRST". arXiv:1412.6097 [astro-ph.EP]..

- [81]

^Unlocking the Secrets of an Alien World's Magnetic Field, Space.com, by Charles Q. Choi, 20 November 2014.

- [82]

^Kislyakova, K. G.; Holmstrom, M.; Lammer, H.; Odert, P.; Khodachenko, M. L. (2014). "Magnetic moment and plasma environment of HD 209458b as determined from Ly observations". Science. 346 (6212): 981–4. arXiv:1411.6875. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..981K. doi:10.1126/science.1257829. PMID 25414310..

- [83]

^Nichols, J. D. (2011). "Magnetosphere-ionosphere coupling at Jupiter-like exoplanets with internal plasma sources: Implications for detectability of auroral radio emissions". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 414 (3): 2125–2138. arXiv:1102.2737. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414.2125N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18528.x..

- [84]

^Radio Telescopes Could Help Find Exoplanets. RedOrbit. 18 April 2011.

- [85]

^"Radio Detection of Extrasolar Planets: Present and Future Prospects" (PDF). NRL, NASA/GSFC, NRAO, Observatoìre de Paris. Retrieved 15 October 2008..

- [86]

^Kean, Sam (2016). "Forbidden plants, forbidden chemistry". Distillations. 2 (2): 5. Retrieved 22 March 2018..

- [87]

^Super-Earths Get Magnetic 'Shield' from Liquid Metal, Charles Q. Choi, SPACE.com, 22 November 2012..

- [88]

^Buzasi, D. (2013). "Stellar Magnetic Fields As a Heating Source for Extrasolar Giant Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 765 (2): L25. arXiv:1302.1466. Bibcode:2013ApJ...765L..25B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/765/2/L25..

- [89]

^Chang, Kenneth (16 August 2018). "Settling Arguments About Hydrogen With 168 Giant Lasers – Scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory said they were "converging on the truth" in an experiment to understand hydrogen in its liquid metallic state". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 August 2018..

- [90]

^Staff (16 August 2018). "Under pressure, hydrogen offers a reflection of giant planet interiors – Hydrogen is the most-abundant element in the universe and the simplest, but that simplicity is deceptive". Science Daily. Retrieved 18 August 2018..

- [91]

^Route, Matthew (10 February 2019). "The Rise of ROME. I. A Multiwavelength Analysis of the Star-Planet Interaction in the HD 189733 System". The Astrophysical Journal. 872 (1): 79. arXiv:1901.02048. Bibcode:2019ApJ...872...79R. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aafc25..

- [92]

^Valencia, Diana; O'Connell, Richard J. (2009). "Convection scaling and subduction on Earth and super-Earths". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 286 (3–4): 492–502. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.286..492V. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.015..

- [93]

^Van Heck, H.J.; Tackley, P.J. (2011). "Plate tectonics on super-Earths: Equally or more likely than on Earth". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 310 (3–4): 252–261. Bibcode:2011E&PSL.310..252V. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.07.029..

- [94]

^O'Neill, C.; Lenardic, A. (2007). "Geological consequences of super-sized Earths". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (19): L19204. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3419204O. doi:10.1029/2007GL030598..

- [95]

^Valencia, Diana; O'Connell, Richard J.; Sasselov, Dimitar D (November 2007). "Inevitability of Plate Tectonics on Super-Earths". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 670 (1): L45–L48. arXiv:0710.0699. Bibcode:2007ApJ...670L..45V. doi:10.1086/524012..

- [96]

^Super Earths Likely To Have Both Oceans and Continents, astrobiology.com. 7 January 2014.

- [97]

^Cowan, N. B.; Abbot, D. S. (2014). "Water Cycling Between Ocean and Mantle: Super-Earths Need Not Be Waterworlds". The Astrophysical Journal. 781 (1): 27. arXiv:1401.0720. Bibcode:2014ApJ...781...27C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/781/1/27..

- [98]

^Michael D. Lemonick (6 May 2015). "Astronomers May Have Found Volcanoes 40 Light-Years From Earth". National Geographic. Retrieved 8 November 2015..

- [99]

^Demory, Brice-Olivier; Gillon, Michael; Madhusudhan, Nikku; Queloz, Didier (2015). "Variability in the super-Earth 55 Cnc e". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 455 (2): 2018–2027. arXiv:1505.00269. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.455.2018D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2239..

- [100]

^Scientists Discover a Saturn-like Ring System Eclipsing a Sun-like Star, Space Daily, 13 January 2012.

- [101]

^Mamajek, E. E.; Quillen, A. C.; Pecaut, M. J.; Moolekamp, F.; Scott, E. L.; Kenworthy, M. A.; Cameron, A. C.; Parley, N. R. (2012). "Planetary Construction Zones in Occultation: Discovery of an Extrasolar Ring System Transiting a Young Sun-Like Star and Future Prospects for Detecting Eclipses by Circumsecondary and Circumplanetary Disks". The Astronomical Journal. 143 (3): 72. arXiv:1108.4070. Bibcode:2012AJ....143...72M. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/143/3/72..

- [102]

^Kalas, P.; Graham, J. R.; Chiang, E.; Fitzgerald, M. P.; Clampin, M.; Kite, E. S.; Stapelfeldt, K.; Marois, C.; Krist, J. (2008). "Optical Images of an Exosolar Planet 25 Light-Years from Earth". Science. 322 (5906): 1345–8. arXiv:0811.1994. Bibcode:2008Sci...322.1345K. doi:10.1126/science.1166609. PMID 19008414..

- [103]

^Schlichting, Hilke E.; Chang, Philip (2011). "Warm Saturns: On the Nature of Rings around Extrasolar Planets That Reside inside the Ice Line". The Astrophysical Journal. 734 (2): 117. arXiv:1104.3863. Bibcode:2011ApJ...734..117S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/734/2/117..

- [104]

^Bennett, D. P.; Batista, V.; Bond, I. A.; Bennett, C. S.; Suzuki, D.; Beaulieu, J. -P.; Udalski, A.; Donatowicz, J.; Bozza, V.; Abe, F.; Botzler, C. S.; Freeman, M.; Fukunaga, D.; Fukui, A.; Itow, Y.; Koshimoto, N.; Ling, C. H.; Masuda, K.; Matsubara, Y.; Muraki, Y.; Namba, S.; Ohnishi, K.; Rattenbury, N. J.; Saito, T.; Sullivan, D. J.; Sumi, T.; Sweatman, W. L.; Tristram, P. J.; Tsurumi, N.; Wada, K.; et al. (2014). "MOA-2011-BLG-262Lb: A sub-Earth-mass moon orbiting a gas giant or a high-velocity planetary system in the galactic bulge". The Astrophysical Journal. 785 (2): 155. arXiv:1312.3951. Bibcode:2014ApJ...785..155B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/785/2/155..

- [105]

^Teachey, Alex; Kipping, David M. (1 October 2018). "Evidence for a large exomoon orbiting Kepler-1625b". Science Advances (in 英语). 4 (10): eaav1784. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav1784. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6170104. PMID 30306135..

- [106]

^Charbonneau, David; et al. (2002). "Detection of an Extrasolar Planet Atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal. 568 (1): 377–384. arXiv:astro-ph/0111544. Bibcode:2002ApJ...568..377C. doi:10.1086/338770..

- [107]

^Evaporating exoplanet stirs up dust. Phys.org. 28 August 2012.

- [108]

^Woollacott, Emma (18 May 2012) New-found exoplanet is evaporating away. TG Daily.

- [109]

^Bhanoo, Sindya N. (25 June 2015). "A Planet with a Tail Nine Million Miles Long". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 June 2015..

- [110]

^St. Fleur, Nicholas (19 May 2017). "Spotting Mysterious Twinkles on Earth From a Million Miles Away". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2017..

- [111]

^Marshak, Alexander; Várnai, Tamás; Kostinski, Alexander (15 May 2017). "Terrestrial glint seen from deep space: oriented ice crystals detected from the Lagrangian point". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (10): 5197–5202. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.5197M. doi:10.1002/2017GL073248..

- [112]

^Forget "Earth-Like"—We'll First Find Aliens on Eyeball Planets, Nautilus, Posted by Sean Raymond on 20 February 2015.

- [113]

^Dobrovolskis, Anthony R. (2015). "Insolation patterns on eccentric exoplanets". Icarus. 250: 395–399. Bibcode:2015Icar..250..395D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.12.017..

- [114]

^Dobrovolskis, Anthony R. (2013). "Insolation on exoplanets with eccentricity and obliquity". Icarus. 226: 760–776. Bibcode:2013Icar..226..760D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.06.026..

- [115]

^Ollivier, Marc; Maurel, Marie-Christine (2014). "Planetary Environments and Origins of Life: How to reinvent the study of Origins of Life on the Earth and Life in the" (PDF). BIO Web of Conferences 2. 2: 00001. doi:10.1051/bioconf/20140200001. Retrieved 11 September 2015..

- [116]

^Kopparapu, Ravi Kumar (2013). "A revised estimate of the occurrence rate of terrestrial planets in the habitable zones around kepler m-dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 767 (1): L8. arXiv:1303.2649. Bibcode:2013ApJ...767L...8K. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/767/1/L8..

- [117]

^Cruz, Maria; Coontz, Robert (2013). "Exoplanets - Introduction to Special Issue". Science. 340 (6132): 565. doi:10.1126/science.340.6132.565. PMID 23641107..

暂无